Seven Septets, Block Design and Imaginary Music

Tom Johnson

I was born in Colorado, in a small town where I didn’t have many opportunities. But I had a very good piano teacher: Rita Hutcherson. Thanks to her, I knew enough to be accepted at Yale University. After that, I became very skilled in sound and orchestration. I could compose, but I wasn’t yet a composer.

So I went to study with Morton Feldman, who wasn’t well known at the time. He couldn’t even teach at a university because he didn’t have a degree. But he was writing very special music, he was a good friend of John Cage, and he knew all the painters. I told myself: he knows a lot, I want to study with this man. I had already worked with every teacher I could find, but it was time to find a master. Each lesson cost $15 — a lot of money for me back then. But I paid it, I “bought” that wisdom, and it was very useful. After two years with him, I had become a composer.

Minimalism in New York in the 1970s was just beginning. I met Phil Glass, Éliane Radigue, Phill Niblock… They were musicians interested in making simple music, breaking away from the post-Webern system. We came from the classical tradition, but we wanted to write music that was thoughtful, well composed.

Probably, my first important pieces are The Four-Note Opera (1972) and One Hour for Piano (1973). These are very minimal compositions, with recurring patterns — always a little the same, always a little different. Einstein on the Beachby Bob Wilson also had a big impact on me, but Deafman Glance was even more decisive. It was even more minimal, and very long. I loved that slowness; it slowed me down, made me want to write longer pieces too.

A few years later, I wanted to bring more logic into my minimalism. I started “counting” the music. When I saw Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Cubes, and some of his other sculptures — both minimalist and logical — I wanted to create something just as beautiful.

What really interests me is the eternal number. I believe that 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 existed before humans, before anything. The logic of numbers is the structure of the world itself; it’s not something invented by humans.

And so, when you study numbers, you discover a great beauty, and that structure can become beautiful music. As a rationalist, I want to approach music rationally. I want to create music that comes from a vague idea, from a dream — and especially not from emotion. I don’t trust my emotions. I want something real, something objective.

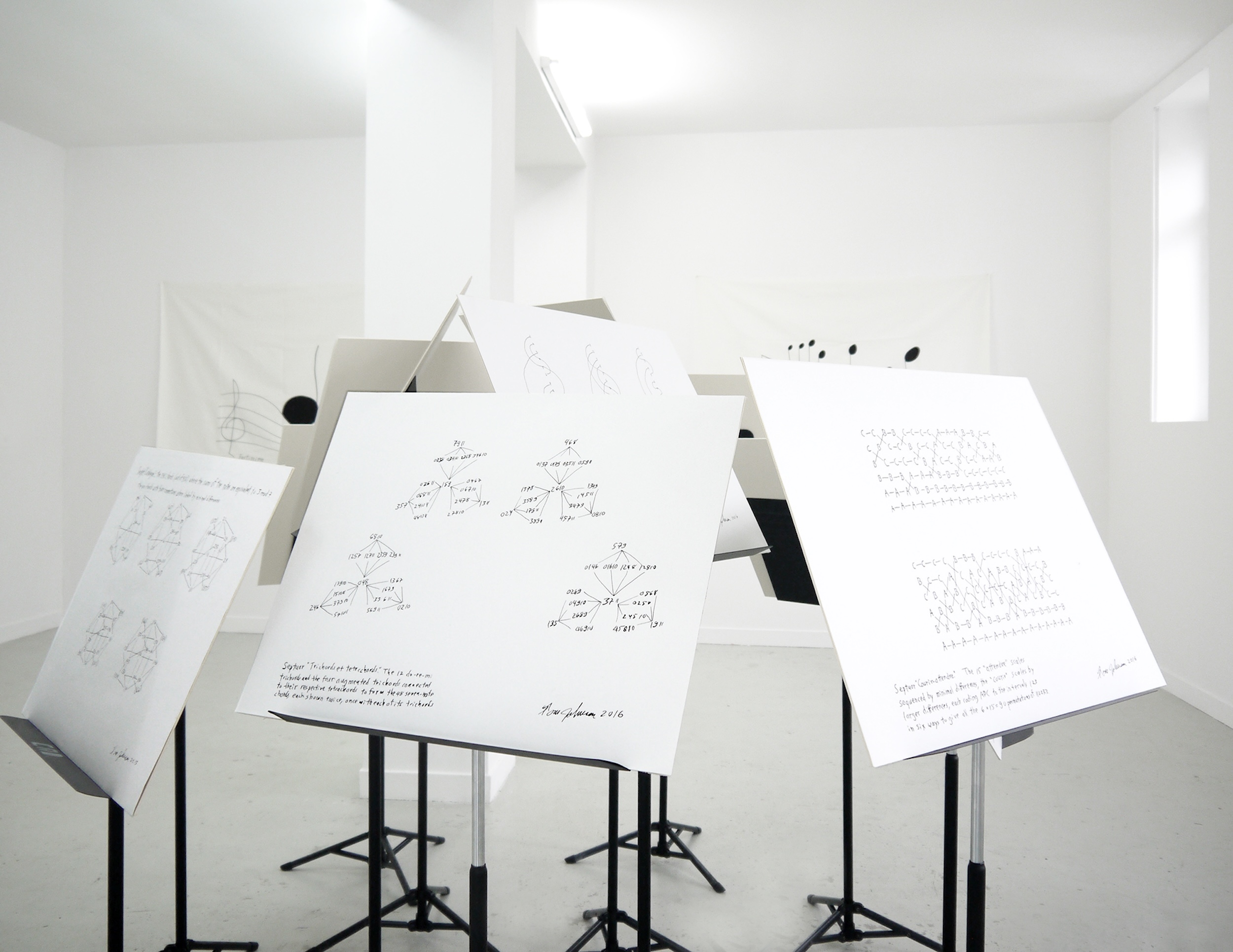

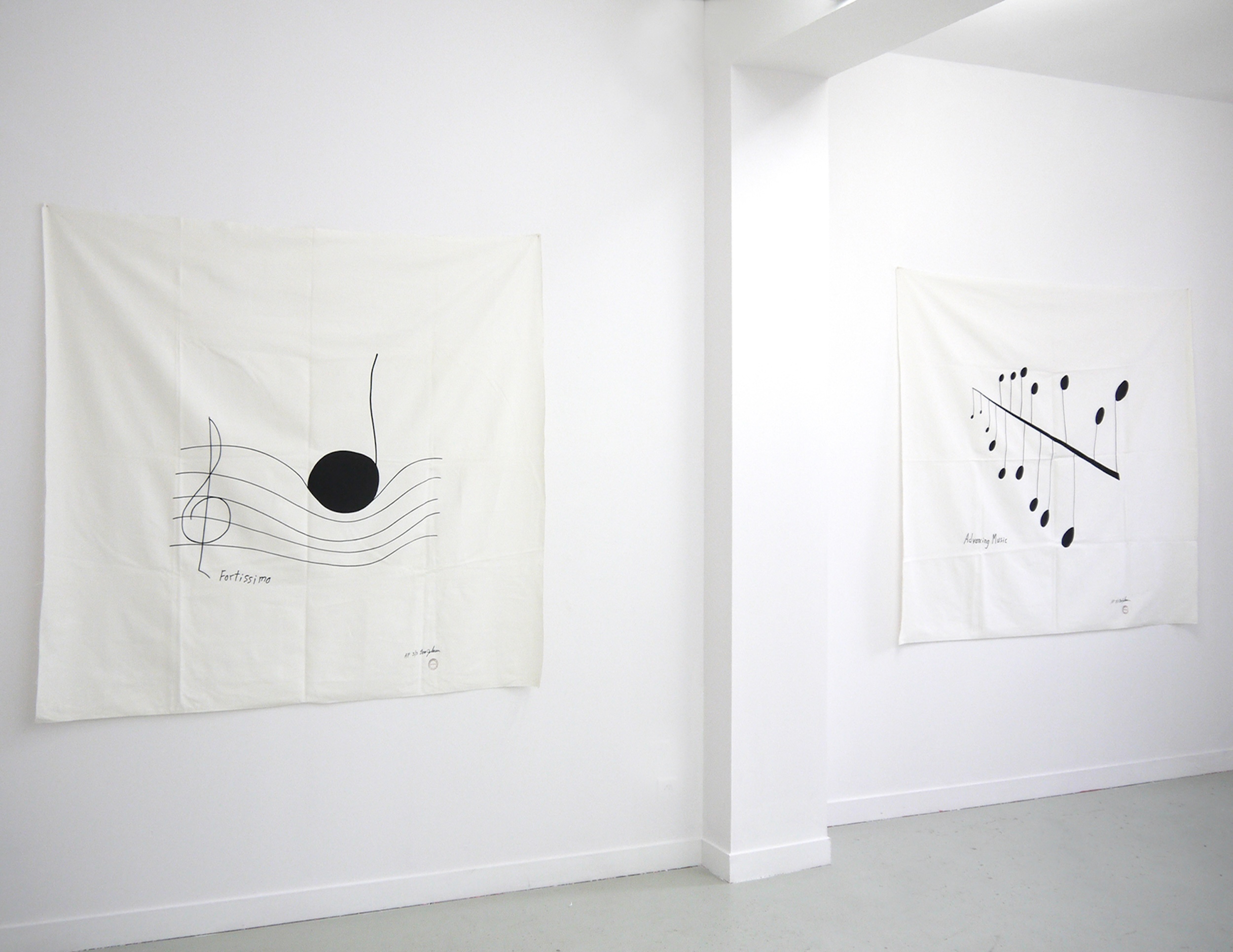

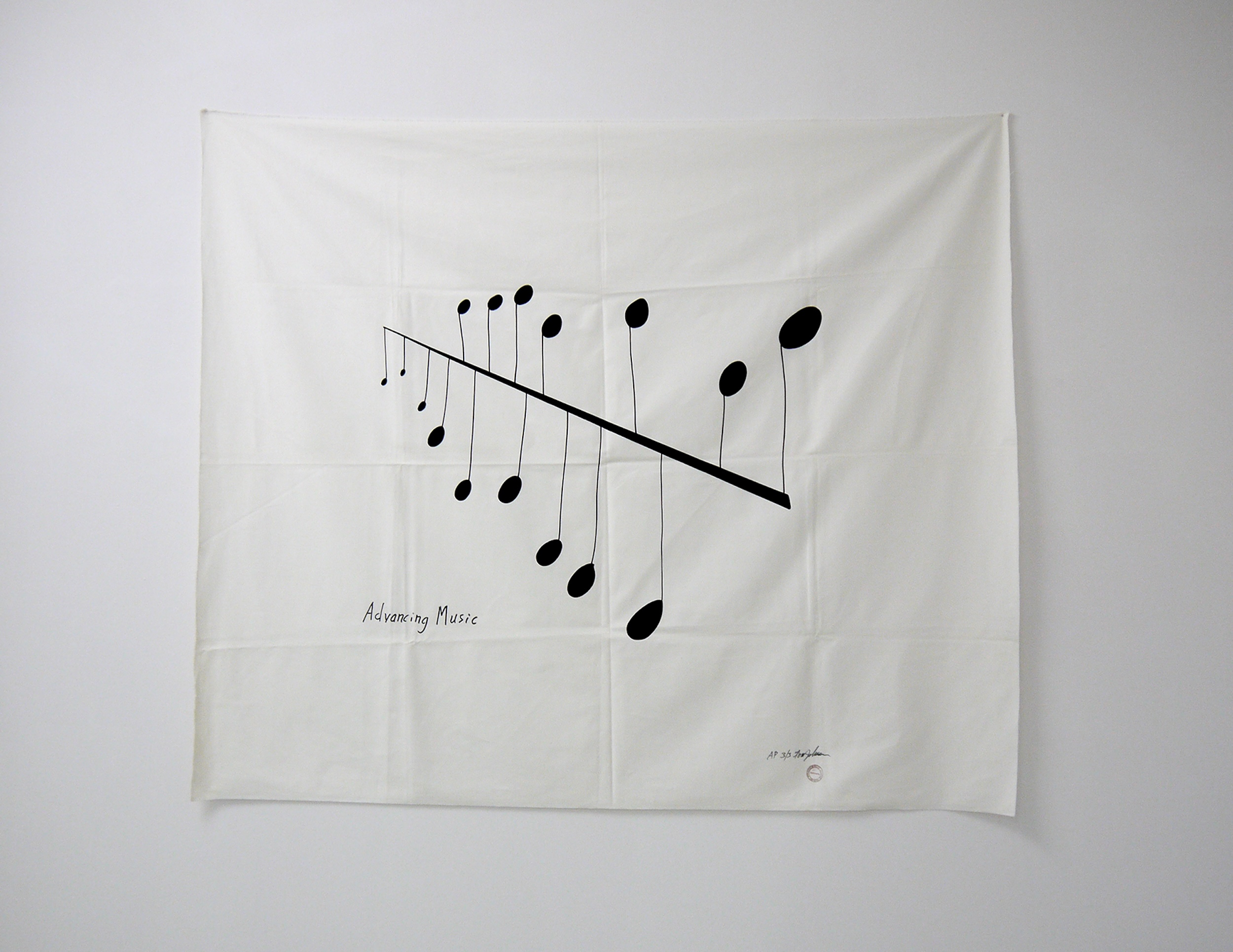

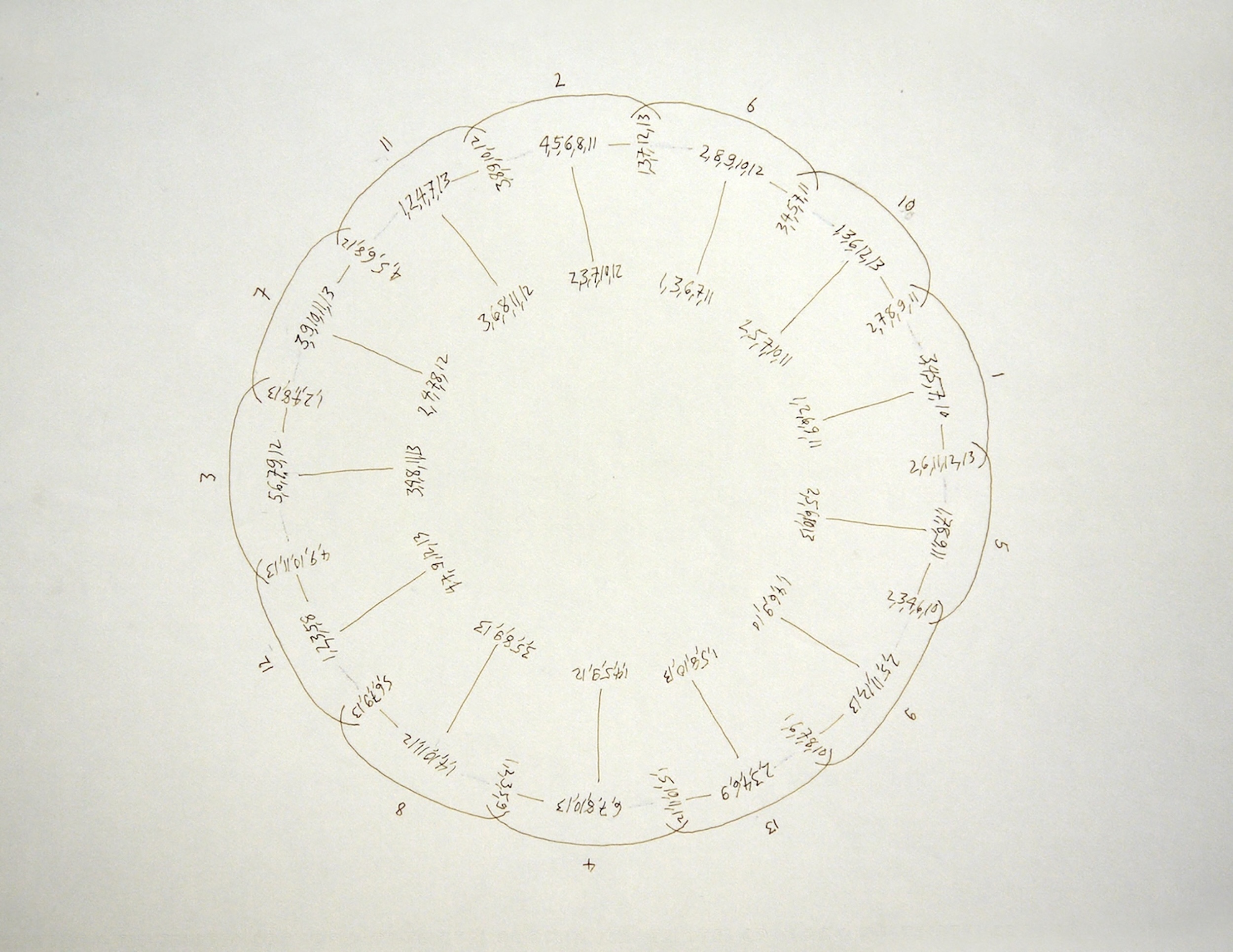

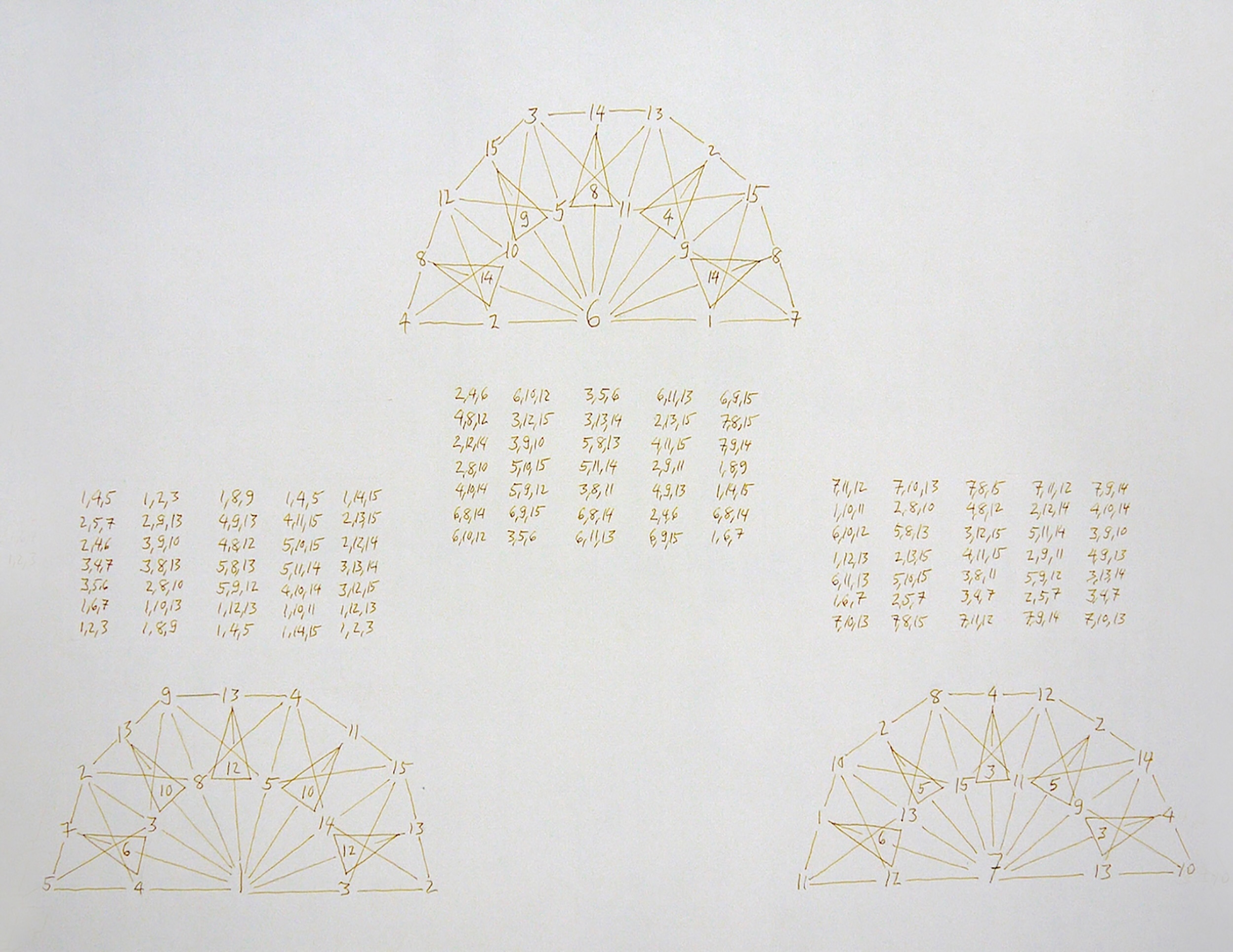

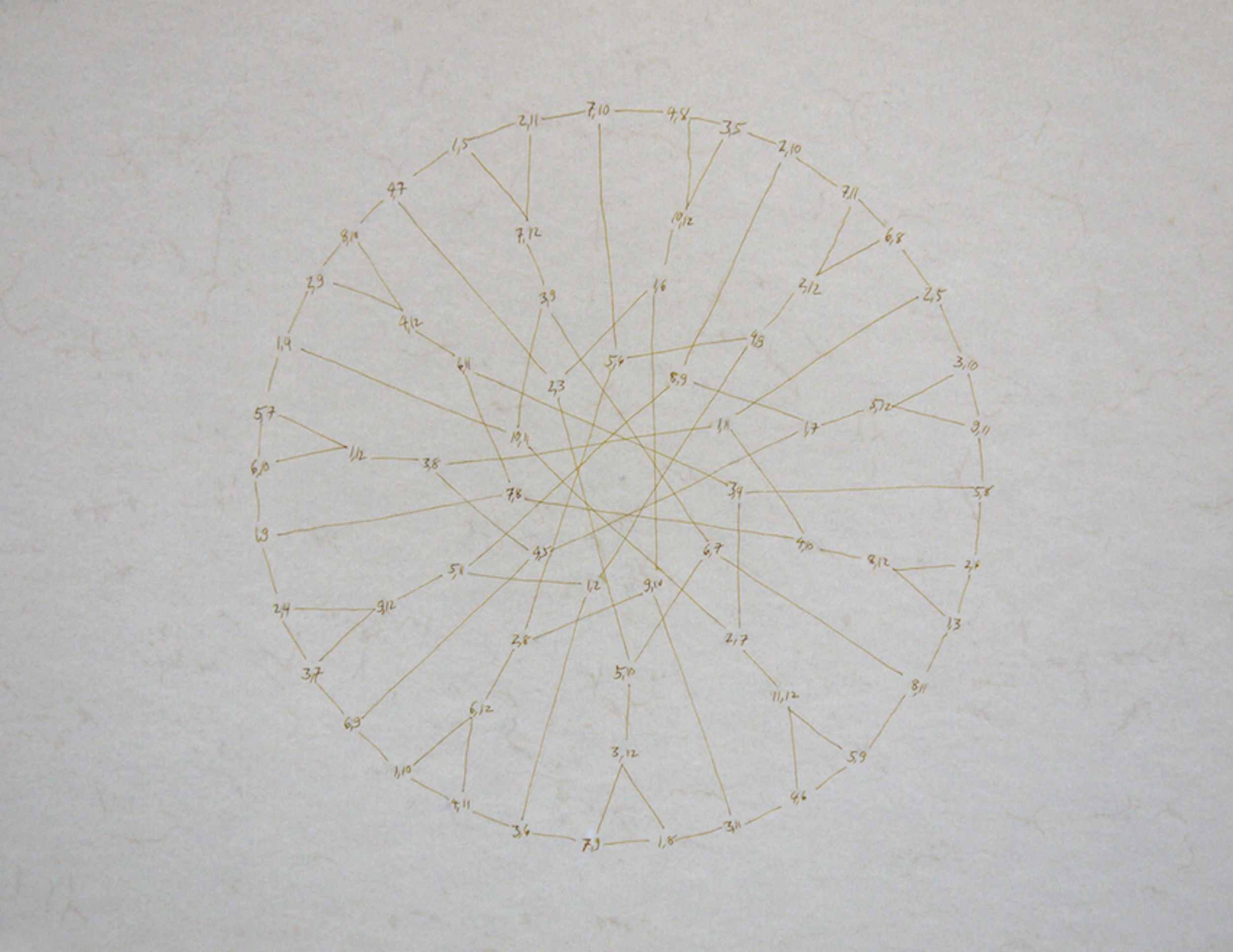

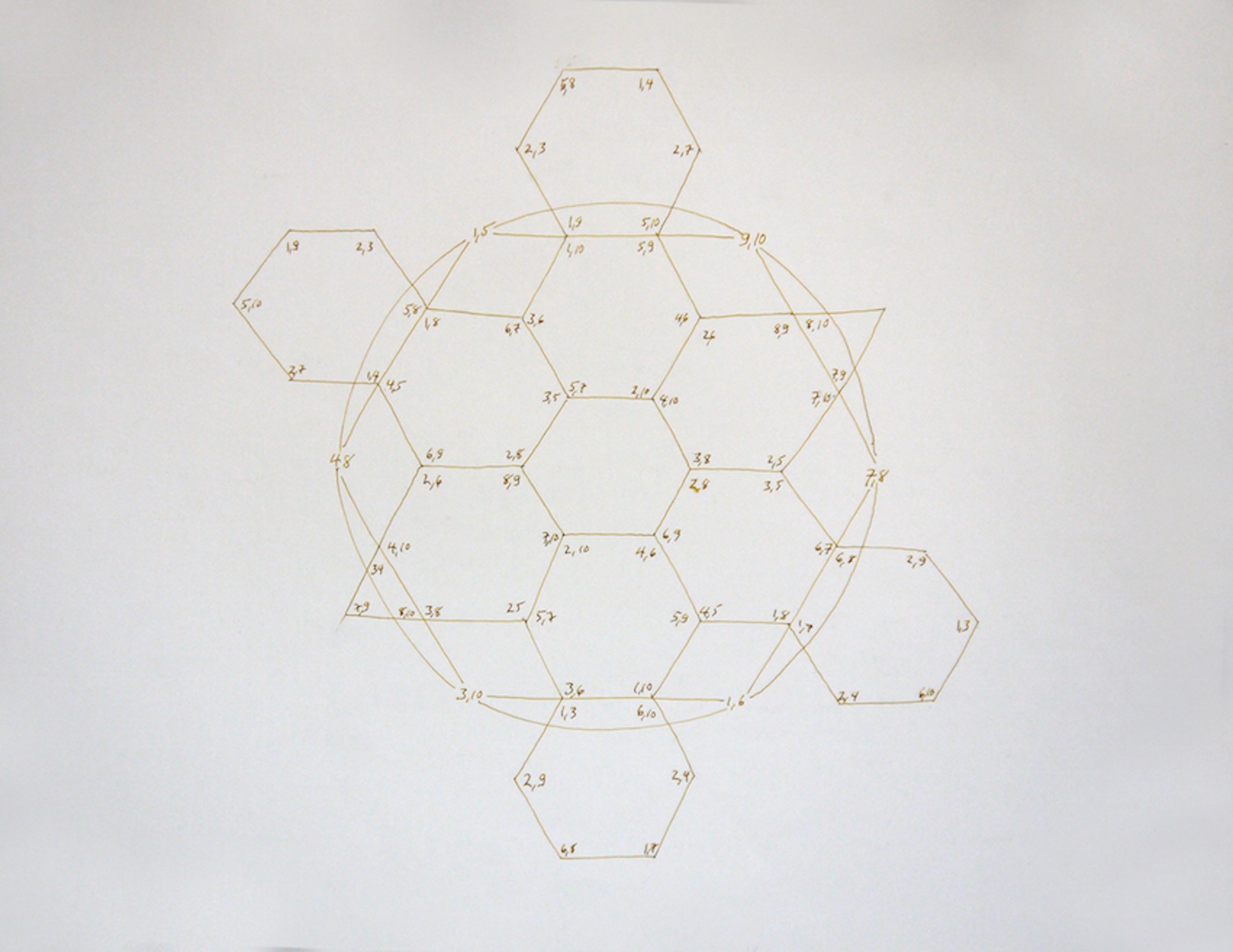

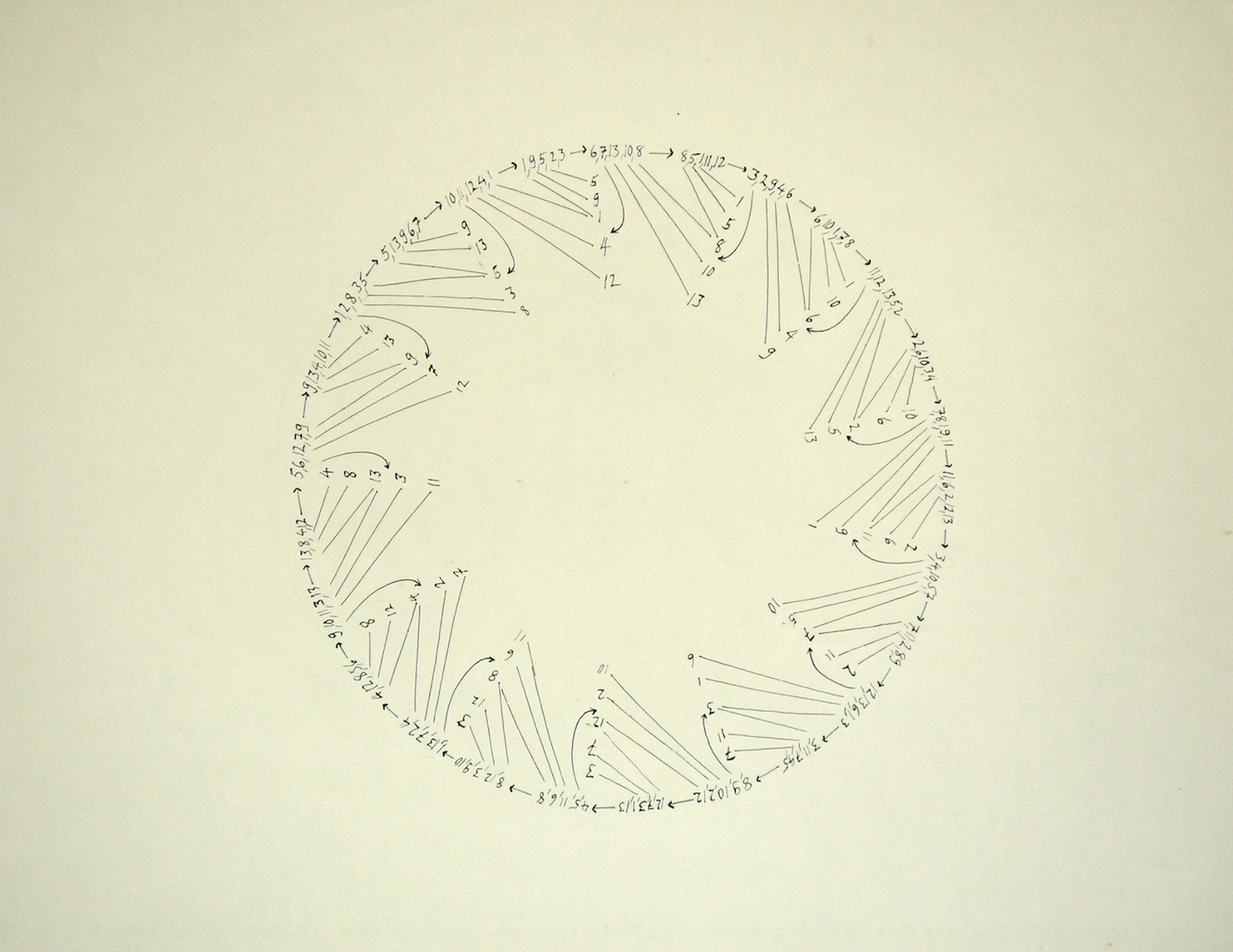

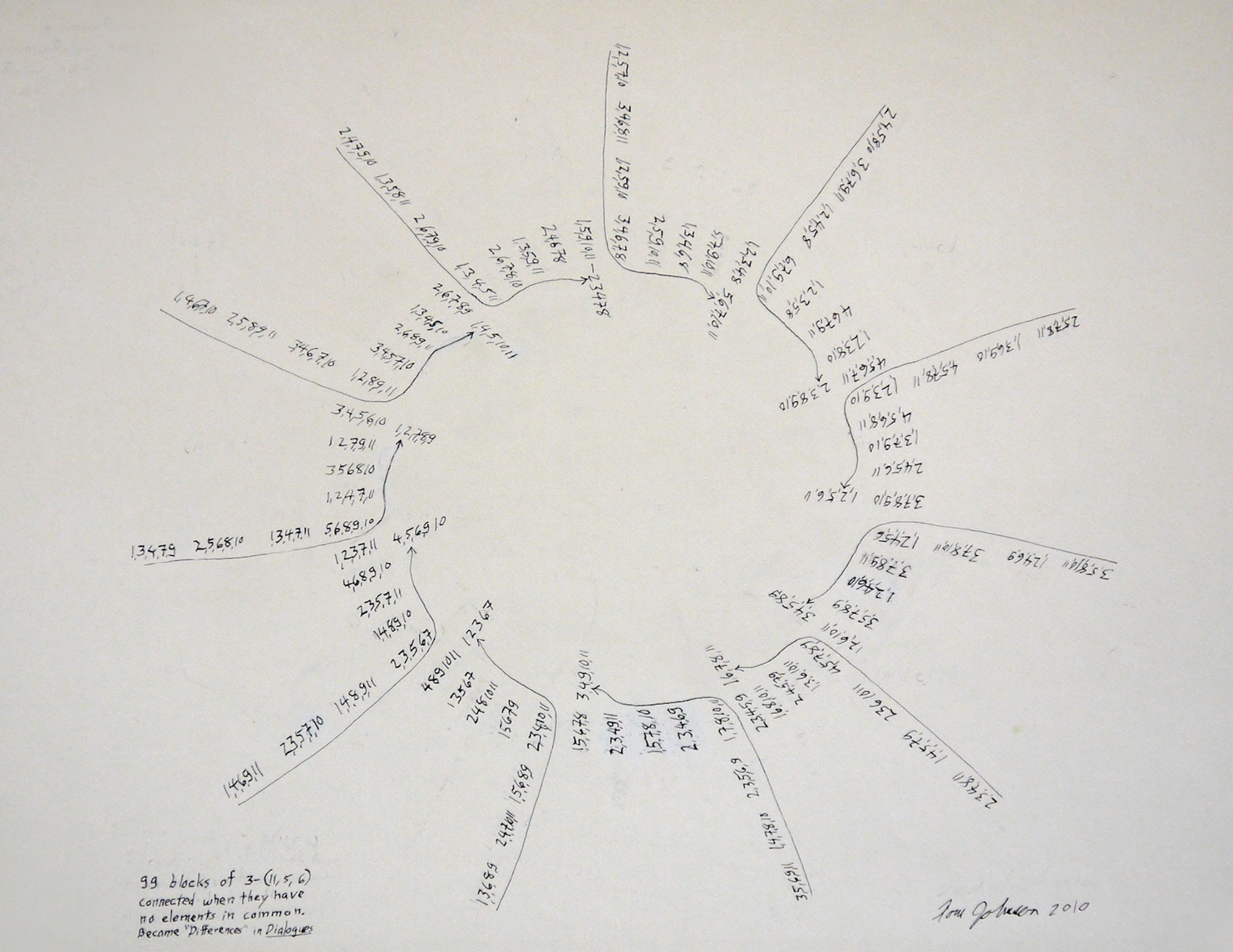

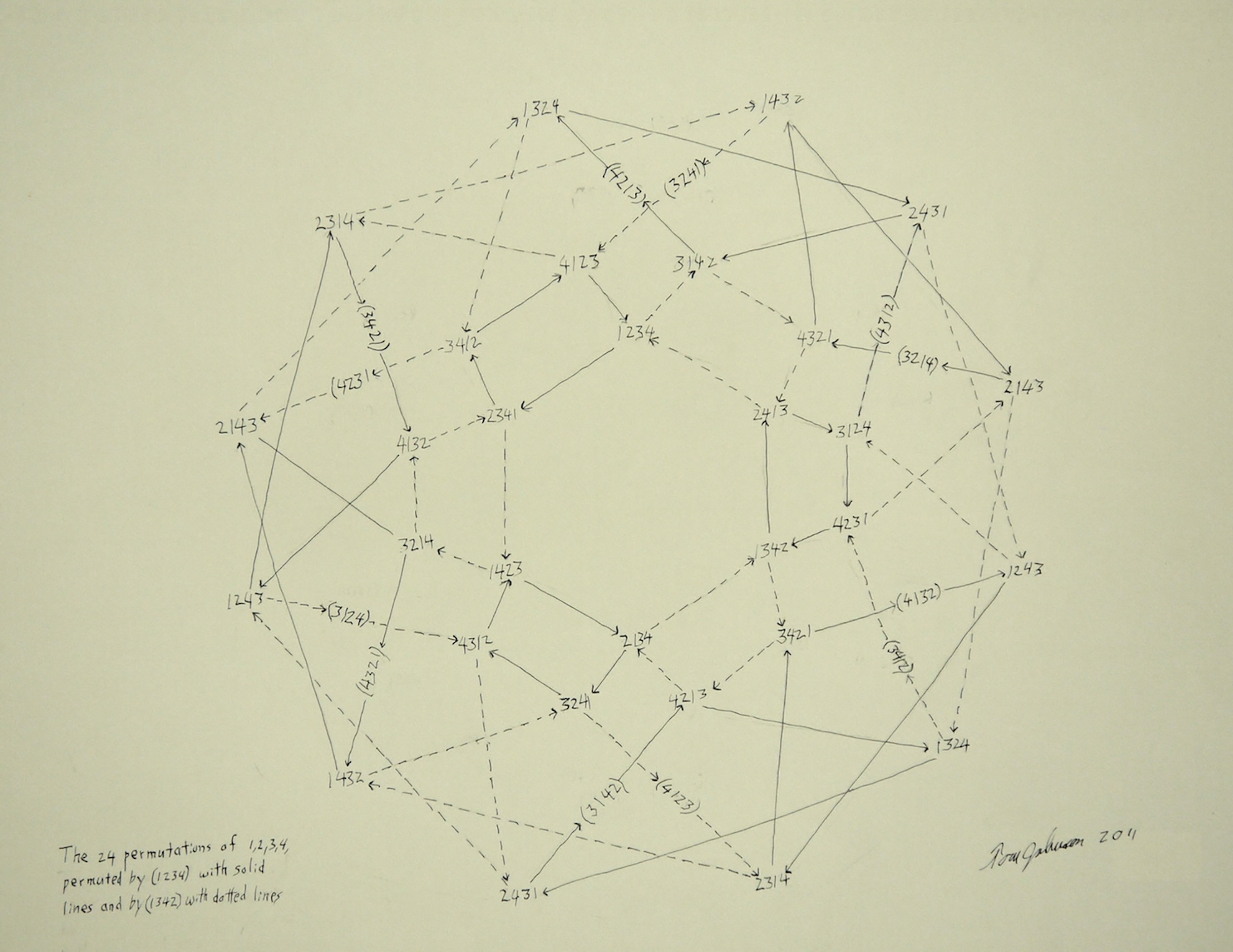

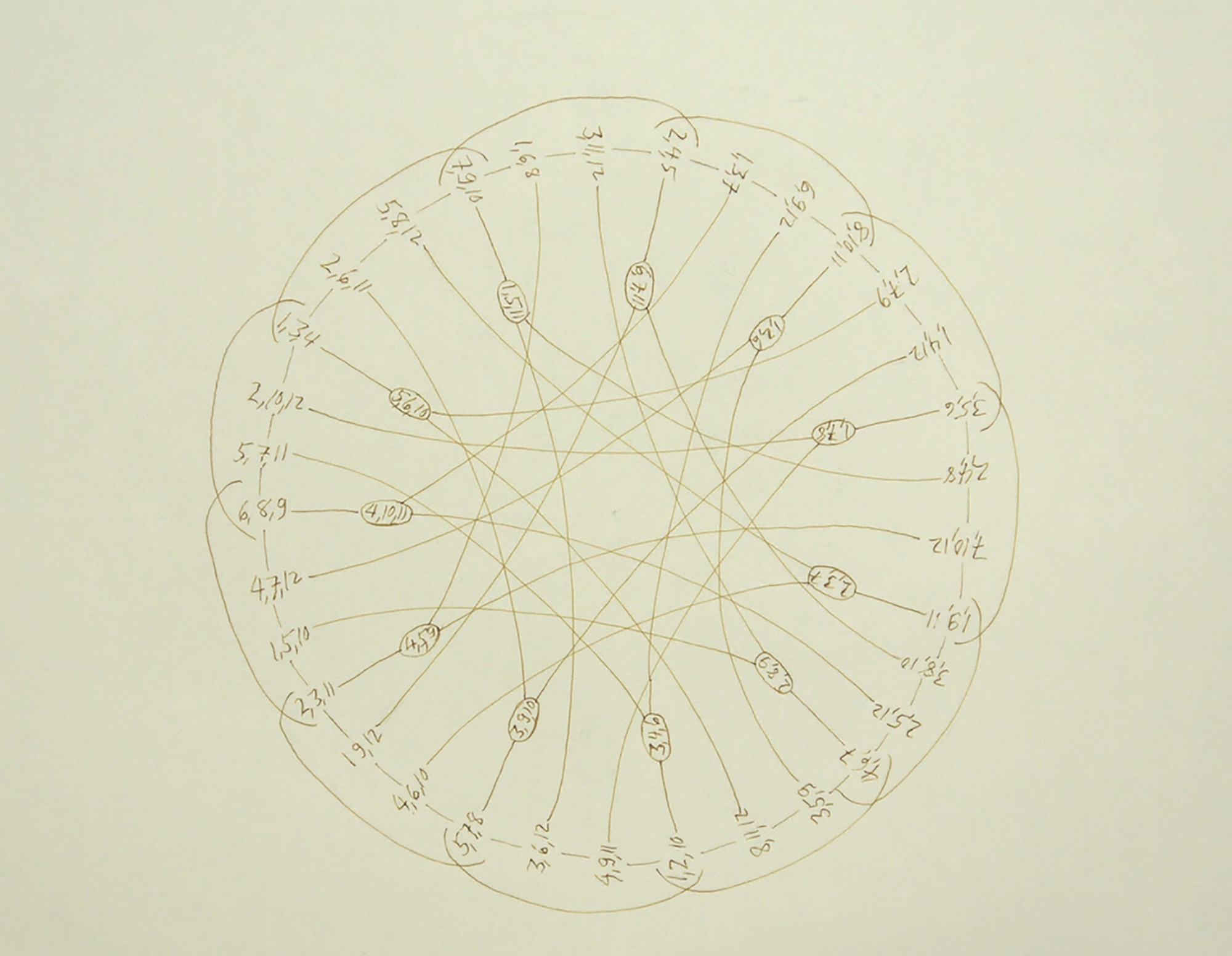

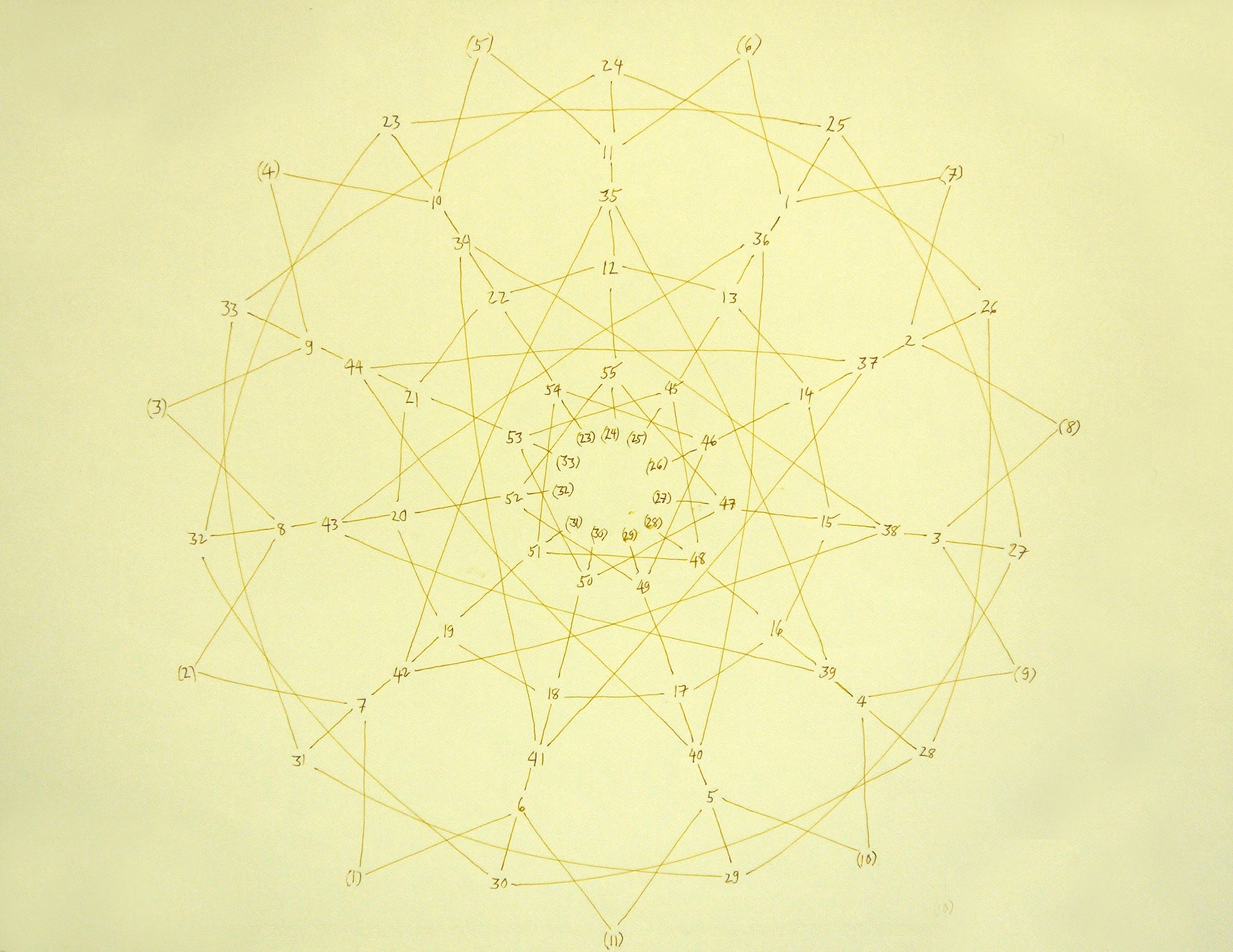

For my drawings, I use something like Block Design. I start from 12 notes, which I divide into subgroups of three (like 1-2-4 or 5-6-9 or 2-6-11…), in such a way that every pair of numbers appears twice within the subgroups. So there are two triplets that include 1 and 2, two that include 6 and 9, two that include 3 and 11, and so on. Then I can create links between the groups of three that share two notes — for example, 1-2-3 can be connected to 1-2-6, 1-3-5, or 2-3-11. But I also use other systems — for example, I take all combinations of three numbers that add up to 17 (1-2-14, 1-3-13, etc.). From there, I create a formation, starting with the lowest number and ending with the highest. There are thousands of ways to create wonderful formations.

The starting point is neither the music nor the drawing, but the mathematics. If there’s an interesting Block Design, I want to draw it, to see what it looks like, what form emerges when I trace all the connections. It all begins with the mathematical structure; then, if I find the right links, it becomes a drawing — and if all goes well, it becomes a piece of music.

But often, I can’t find a musical translation. I still make the drawing, and if the number sequences are beautiful, if I can appreciate them visually and logically, I keep them. Fortunately, many drawings also become good pieces of music — but not always. In this exhibition, for example, there are many drawings that aren’t musical and probably never will be… unless someone else finds the translation that I haven’t discovered myself.

One of my most appreciated pieces is The Cows of Nariyana. It’s a logical sequence that comes from a 14th-century Indian mathematician, from a time when mathematics wasn’t as technological as it is today. For this beautiful piece of music, I’ve never found a drawing. I can’t draw it, I don’t know how. You can make tables or graphs, but it’s not beautiful as a visual system. Sometimes logic is visual, sometimes musical, sometimes both — and sometimes neither.

But that’s how it is. I keep searching for order in the numbers.