Misty the Fox

Jordan Derrien

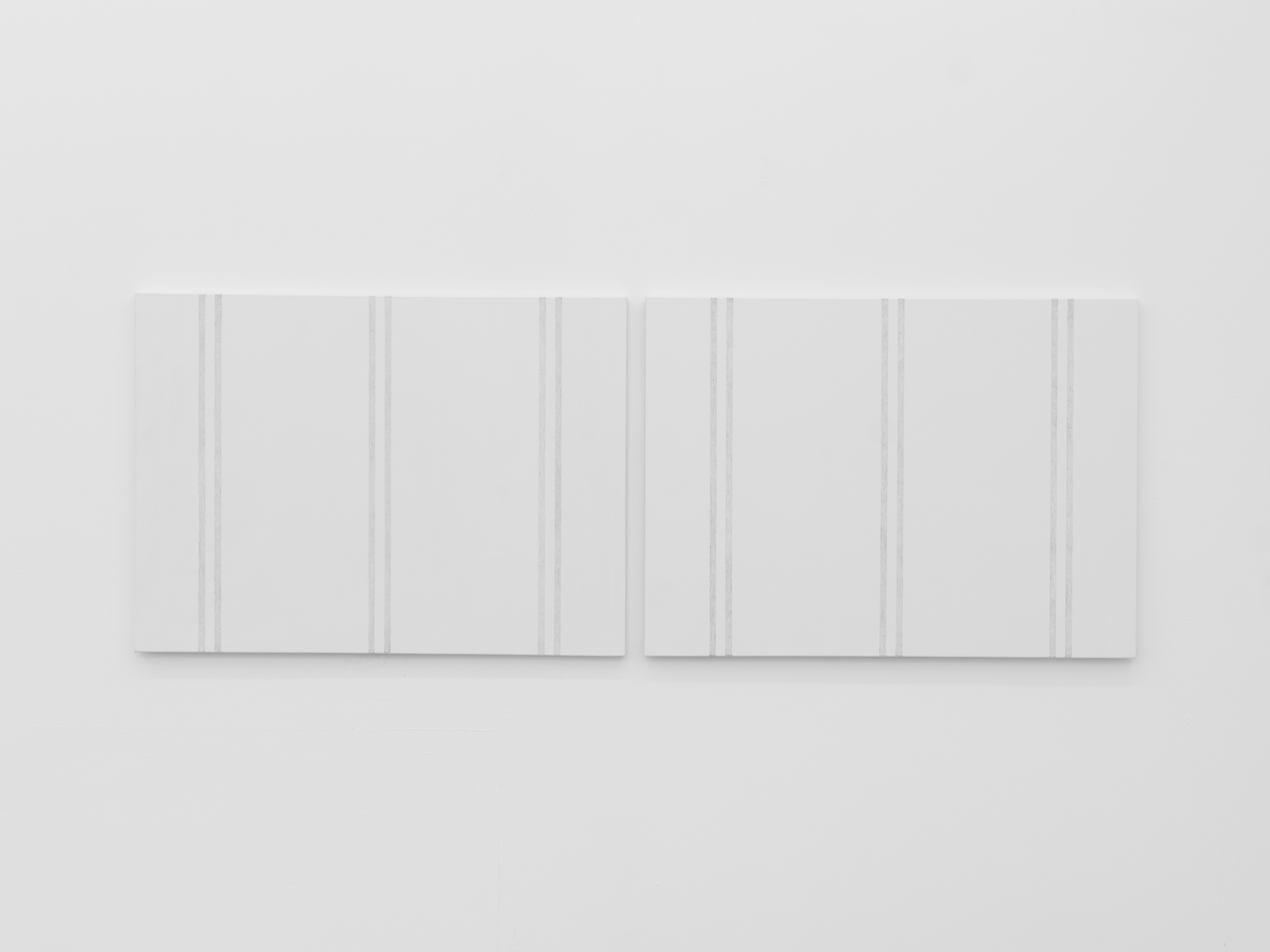

Untitled, 2025, graphite, oil based paint on canvas 56 x 76cm, photo : Daniel Browne

243 Northdown Road (A), (B), (C) , 2025 acrylic on canvas 20 x 180cm, photo : Daniel Browne

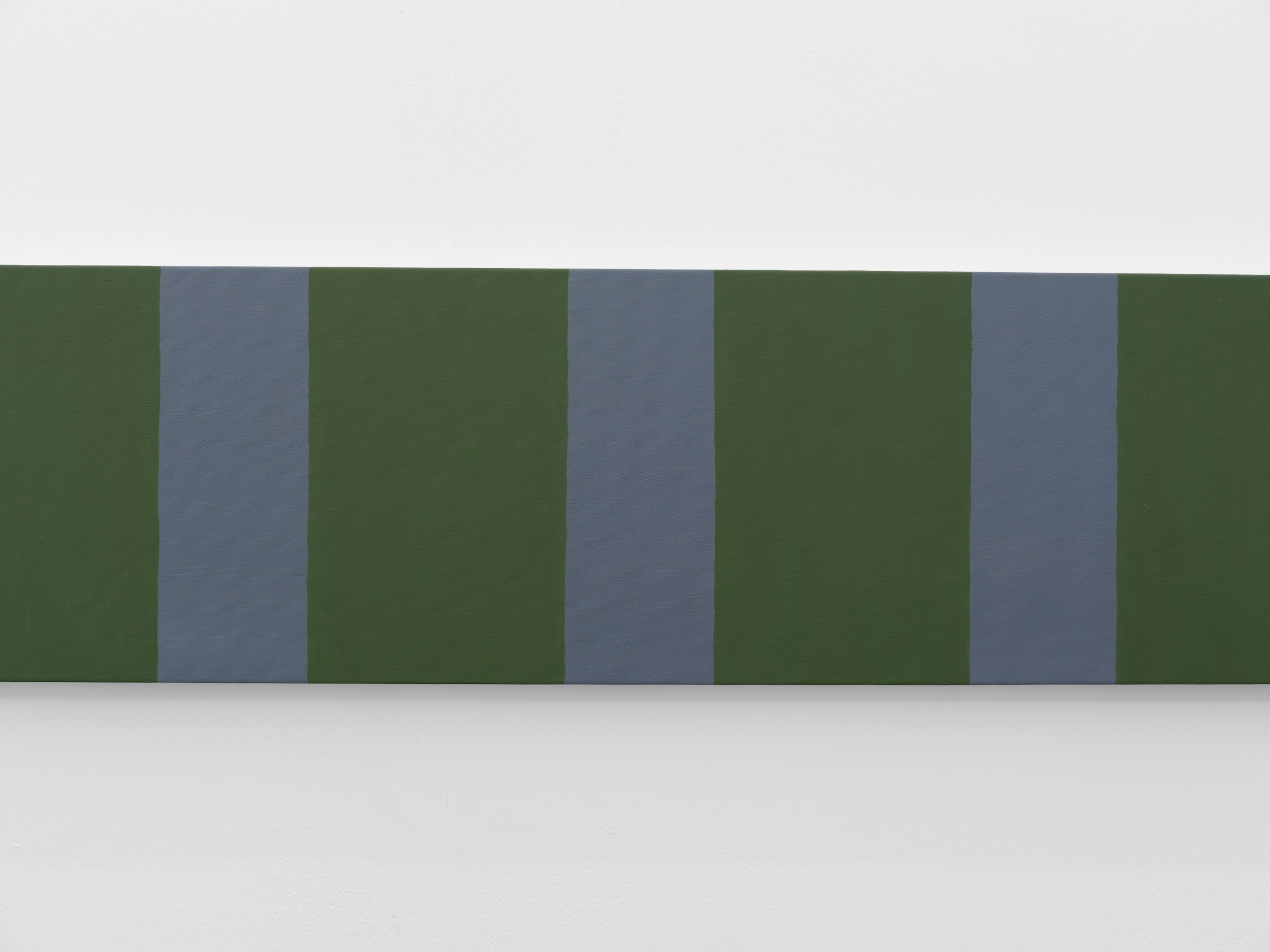

243 Northdown Road, 2025 acrylic on canvas 12 x 180cm, photo : Daniel Browne

“An expensive variety of wallpaper,” John Updike once scoffed, describing a painting by Richard Diebenkorn.¹ This use of wallpaper as a sneer embodies much of the medium’s historical ambiguity. For centuries, there was no clear hierarchy between the decorative and fine arts. In the sixteenth century, for example, Albrecht Dürer designed wallpaper motifs with the same seriousness as his woodcuts, considering everything he made to be ‘fine art’ intended for wide and inexpensive distribution.² However, with the Industrial Revolution came impersonal mass decoration, and the idea gradually emerged that decoration was less valuable. Since wallpaper became broadly available, its status has been debated: is it background or foreground, surrogate or the real thing, art or decoration?³

A similar tension is reflected in the history of painting. The Symbolists and Fauvists deliberately chose a decorative style in order to move beyond mimetic representations of the visible world and explore the expressive potential of colour and form. Maurice Denis celebrated Paul Gauguin as a ‘decorator’, creating art with flat colour and precise contours that was according to Denis closer to tapestry or stained glass than oil painting. At the same time, however, abstract painting was haunted by the fear of becoming mere decoration. Clement Greenberg summed this up by saying that “decoration is the specter that haunts modernist painting,” and argued that part of the task was to use “the decorative against itself.” Late Impressionism and Fauvism only exacerbated this tension, with decorative means serving non-decorative ends.⁴

Jordan Derrien sets out from that ambivalent legacy. His proposition is radically simple: What if painting was nothing less than wallpaper? What if painting equal wallpaper? As you enter the exhibition space, a diptych on the left presents motifs that appear as pencil traces on white painted canvas. On the right is a long, horizontal series of successive colour fields, arranged in a rhythmic pattern. The paintings are composed of alternating vertical bands of green and grey. The green paint has been applied over a grey primer, deliberately leaving the background visible to give the rhythm extra depth. In the middle of the wall, a narrow vertical painting interrupts the horizontal movement. This piece appears monochrome, with the green covering the entire grey base layer, creating a single, concentrated strip. Its width precisely matches that of a single green band in the sequence. These works behave like portable walls, doubling the continuum normally occupied by wallpaper. In doing so, the exhibition reverses the logic of wallpaper through painting, letting two skins slide over one another — the skin of the wall (wallpaper) and the skin of the canvas (paint) — until they coincide. Inspired by Regency designs, the wallpaper anchors the whole exhibition in a domestic, historical idiom. The function and connotation of these interventions drive a continual exchange between domestic and pictorial space, articulating a passage from material to medium.

Looking at the works, associations with Barnett Newman come to mind. In his paintings, the monochrome colour field appears as a pictorial space defined by the boundaries of the canvas. His narrow vertical band, the so-called ‘zip’, activates the field semantically. This band acts as a drawing that does not define contours, but rather articulates space. It is a unique occurrence that enables the entire field to communicate and implies a transcendent order. The field and the zip determine each other; the finite as opposed to the infinite.⁵ The band operates differently with Derrien. His stripes are not an ontological incision, but rather a repeatable pattern or frieze. Instead of opening up the space metaphysically, they measure it and choreograph attention rather than sublimating the field. Thus, the band changes from an absolute definition of the entire space to a relational one: a rhythmic indication that makes us feel that the whole encompasses not only the canvas, but also the space in which it is displayed. In this way, Derrien reverses Greenberg’s imperative, using the decorative not “against itself” but for itself as an instrument to make the boundary between pictorial autonomy and architectural embedding tangible.

Derrien’s paintings occupy the middle ground between ‘looking at a canvas’ and ‘seeing a wall’. The pictorial is still influenced by the logic of decoration and functionality, while the decorative is transformed into an image. This means that the distinction between background and foreground, and between art and decoration, is not a matter of choice, but a working principle. Rather than behaving like a window or a mirror, the painting acts here as a barrier that both reveals and withholds; by the simple fact of being hung, it covers a section of wall and activates what lies behind it. Derrien makes concealment productive, revealing by covering and protecting what his surfaces contain. Thus, the painting becomes a barred window, reframing the view. Meaning does not arise on the canvas itself, but in the zone where wall and painting become each other’s skin.

Pieter-Jan De Paepe

¹ John Updike, “Just Looking”, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), p. 115

² Marilyn Oliver Hapgood, ”Wallpaper and the Artist: From Dürer to Warhol”, (New York: Abbeville Press, 1992), p. 9

³ Lesley Hoskins, ”The Papered Wall: The History, Patterns and Techniques of Wallpaper”, (London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2005), p. 6

⁴ Christine Mehring, “Decoration and Abstraction in Blinky Palermo’s Wall Paintings”, Grey Room, vol. 18 (2004), p. 99

⁵ Paul Crowther, “Barnett Newman and the Sublime”, Oxford Art Journal, vol. 7 (1984), pp. 55-56