Daytime TV

Ludovic Sauvage

“Oedipa stood frozen in the middle of the living room, under the cold, greenish eye of the television. She called upon the Lord in vain and tried to feel as drunk as possible. It didn’t work.”

– Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49

To inhabit images as though stepping into a reversed space, where spectral figures and sketched gestures might trace the possibility of a counter-world. The aim would be to overturn space, provoke vertigo, and suggest the drifting of an inverted reality. Indeed, space and time traverse the image in Ludovic Sauvage’s work, serving as the point of departure for fractured forms. Daytime TV might be read as a narrative made of alcoves hidden beneath reality, of absences and presences, their substance scattered here and there. Toward a sensitive and codified space where each surface reflects as much as it absorbs, and where every element replays its own revelation.

A mise en abyme that could be linked to what certain critics have called “metafiction” as a literary genre[1]. In its postmodern extension, fiction—beyond strategies of self-reference[2], pastiche, and citation of previous genres[3]—acts as a reflector of the structures shaping our relation to the world. It seeks, through the absurdity of its scenario, to paradoxically grasp the texture of reality. During the same 1970s–1980s period, this taste for archetypal appropriation became a hallmark of the Pictures Generation, whose critical impulse sought to unearth the simulacrum inherent in mass media. But it was the artists of the 1990s who would insert themselves into the fictional process, extending it to the exhibition space itself—conceived as a transitional space[4], suddenly ready to exalt reality. As in literature, fiction as a tool brings to light the degrees of agency in our relationship to the real. These formal juxtapositions create a porosity between the illusory and the real, intensify what surfaces, and convey an intimacy with the world. But what might a metafiction look like if it shifted from a literary genre to concrete forms—applied to the materials of the real?

It is perhaps from this intuition that Ludovic Sauvage has, over time, conceptualized an installation practice where images take form through their deconstruction within space. Each gesture grants them autonomy and causes a temporal shift, as they become in turn moment, object, or pure surface. From metafiction, the aim is no longer to pastiche but to inhabitimages. If he extracts a stock of stereotyped motifs, torn from their context, it is to generate a malleable material and extrapolate it into new situations—dilating the atmosphere of a world punctuated by inconsistencies, where every form seems to flirt with the real and give it a closer taste. The gesture thus injects the images with a formal, seductive presence that remains elusive, positioning them slightly out of time.

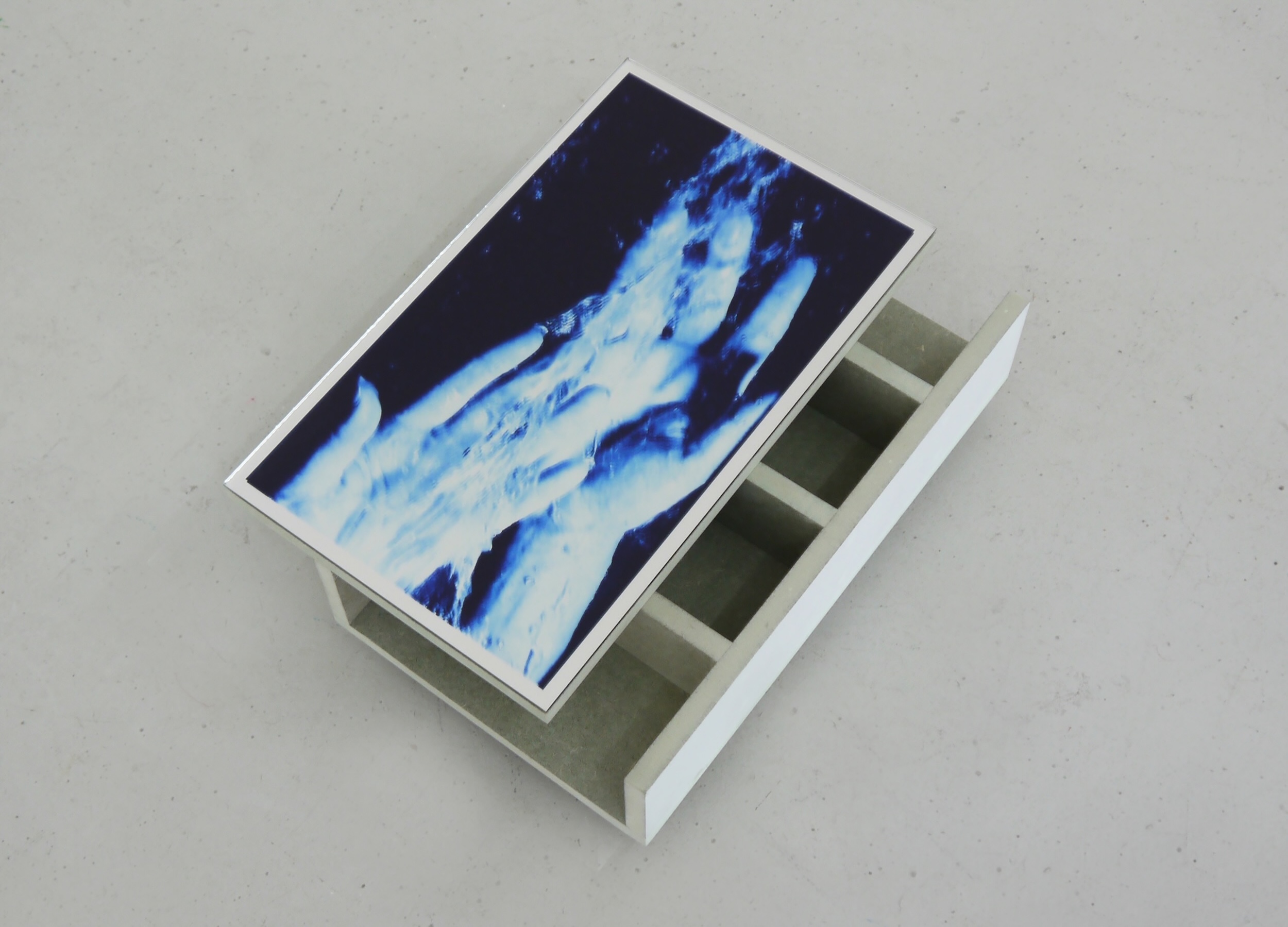

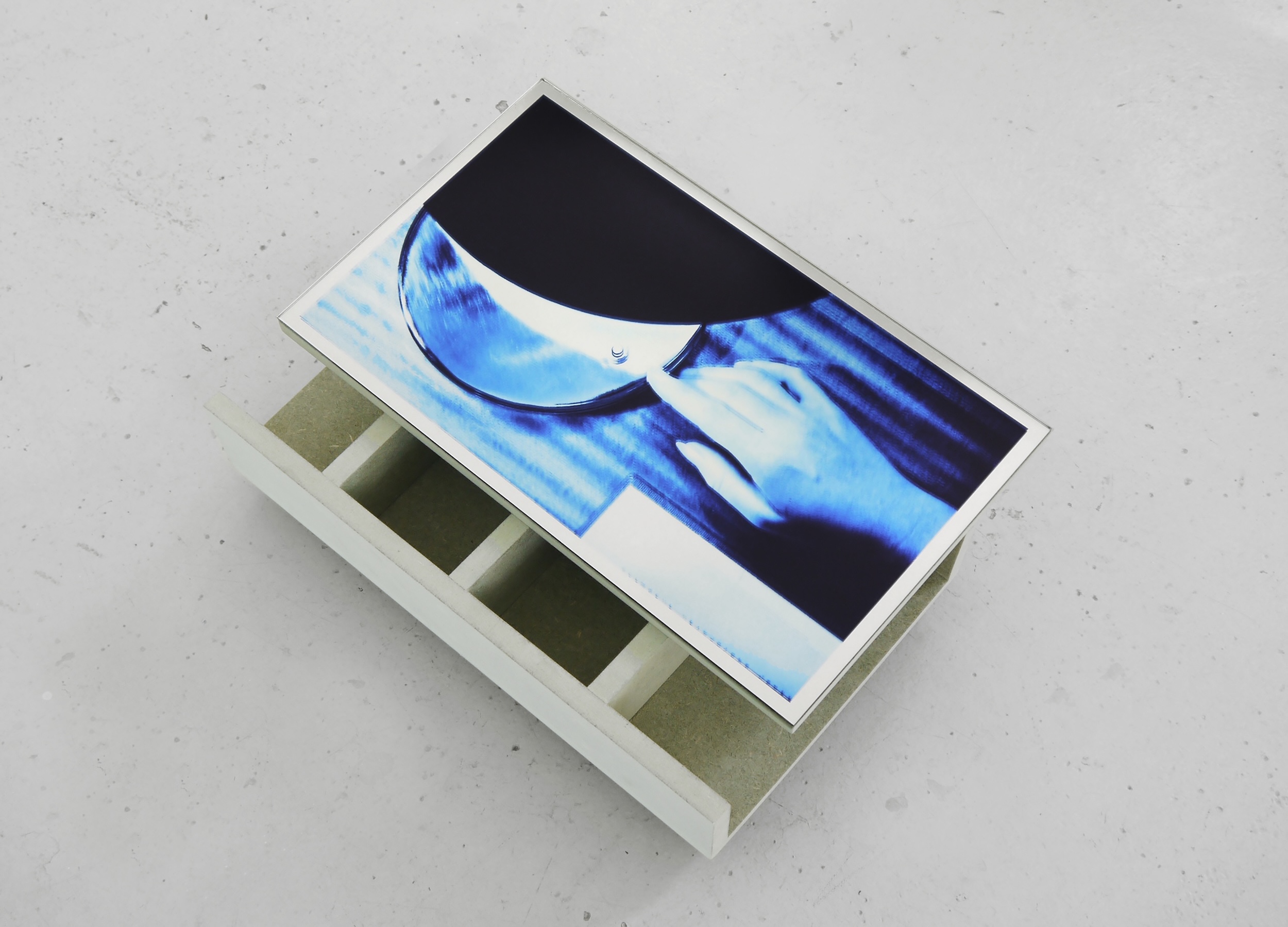

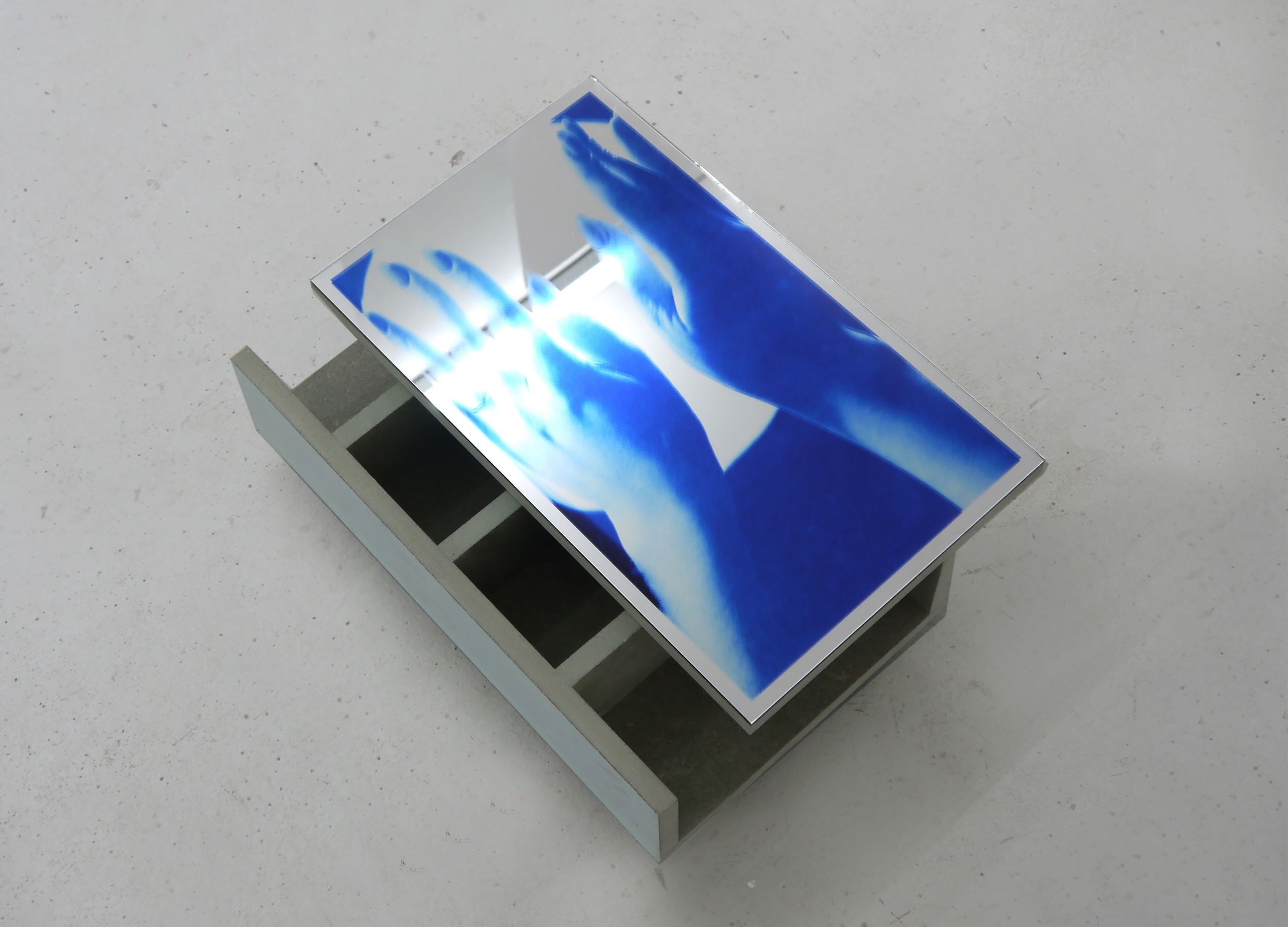

Daytime TV is no exception to this process of appropriation, where the simulacrum is now stretched to the edge of abstraction. Sauvage infiltrates the image—except here, he forgoes a direct use of light in favor of detours through the object. Beyond images, fragments of furniture spread across the exhibition space. Perched on waterproof wooden modules—a distant nod to the original function of Les Bains-Douches—these surfaces are no longer static planes but transitional ones, their images incarnated on mirror-screens. On the floor, printed mirrors might illustrate, like chapters, domestic manipulations tinged with a charming strangeness, the touch of blue velvet remaining intangible. Inserted into modules, always offset from their structures, these works suggest an unveiling of the image, like a drawer of concrete shadow releasing a reality that is sometimes silent, barely hidden. On the walls, cottony specters nuance and weigh down the atmosphere with violet mist, printed in gradients on sliding mirrors. Yet here, mirrors are no longer meant to enlarge space but rather to blur it—already situated in an in-between stage. The blue perforated and embedded surfaces—a recurring motif-tool in the artist’s work—project a missing part: the vanished image, now only reflecting the inverted space one must surrender to and dive into. It’s up to us to let ourselves be pulled in, to settle in the darkness of the off-screen. So much so that the disappeared image reappears elsewhere, illuminating another interior—on the reverse of a hanging jacket.

At Les Bains-Douches, Ludovic Sauvage materializes a perceptual loop that evokes reality as much as it leads us astray: a kind of temporal ellipse replacing the linearity of time. Each form emancipates itself even as it contributes to the exhibition’s totality. The mirrors endlessly place the screen of the real into a mise en abyme, crossing through it and surrounding us with it. If the initial meaning of the image dissolves, it is in favor of a new receptacle—an eternal loop. Now incarnated in the mirror, the images make us question the objectivity of the mirror itself, no longer destined to reflect what we cannot perceive, but transfiguring its presence into an instrument of self-revelation[5] of what escapes us.

[1] Notably American authors, including among others: Thomas Pynchon, Robert Coover, and William H. Gass.

[2] GASS, William H., Fiction and the Figures of Life, New York, Knopf, 1970. Gass outlines a literary genre of fiction that engages in mise en abyme and critiques its own form within the narrative itself in order to present a secondary discourse.

[3] WAUGH, Patricia, The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction, London/New York, Methuen, 1984.

[4] FROGIER, Larys, “Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno,” Critique d’art 13, Spring 1999.

[5] DANTO, Arthur, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1989, p. 41.