other people’s clothing

Kevin Desbouis, Pati Hill, Charlotte Houette

Une proposition de Fiona Vilmer

11.03 – 24.04.2022

Kevin Desbouis, Untitled (Moist), 2022, voting booth, finger moisteners, cotton, 200 x 80 x 80 cm

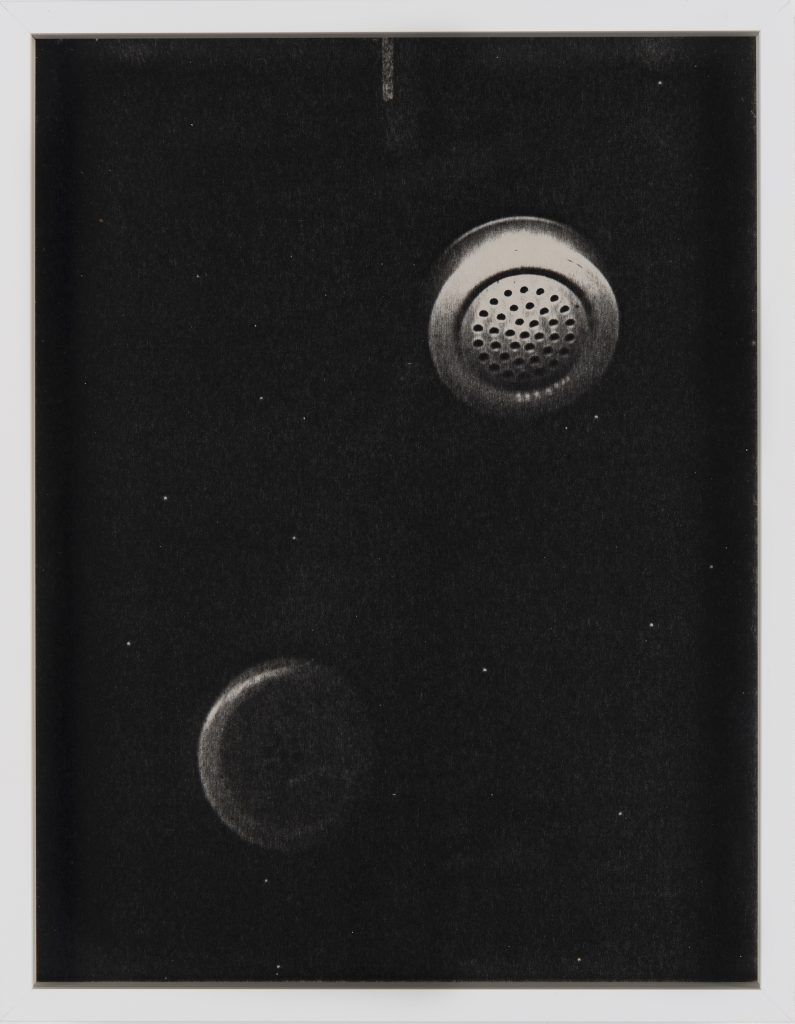

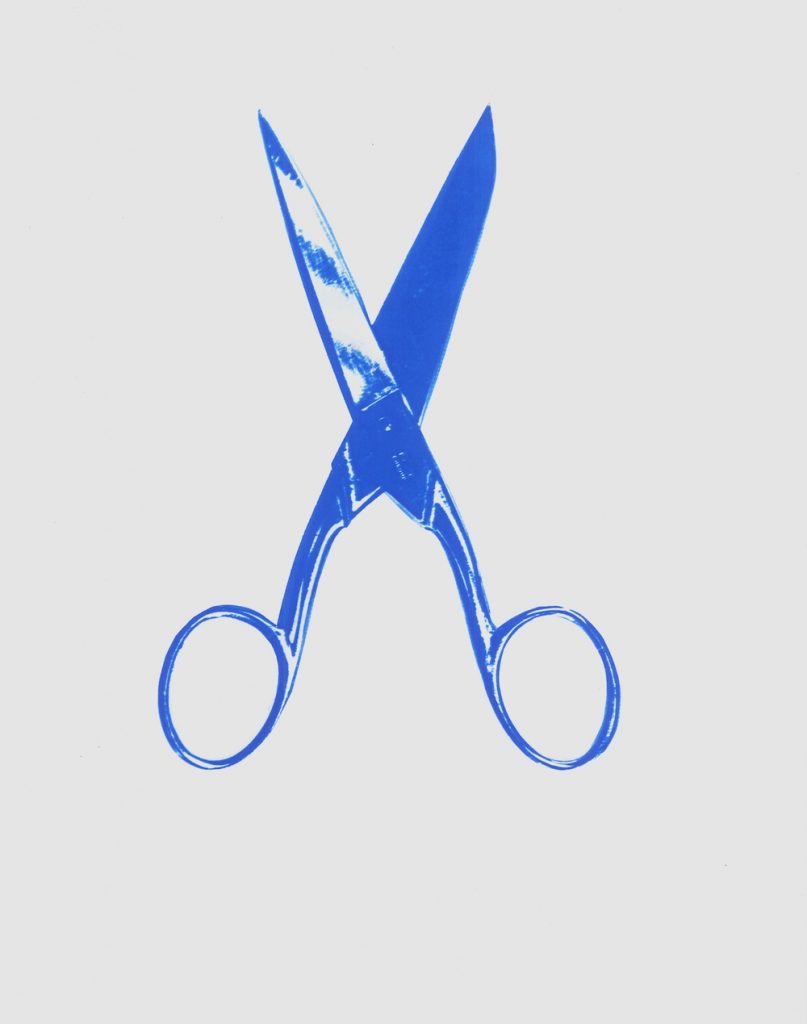

Pati Hill, Untitled (telephone), c.1977-79, serie (Common Objects), photocopy, 28 x 21,5 cm

Kevin Desbouis, Untitled (Moist), 2022, voting booth, finger moisteners, cotton, 200 x 80 x 80 cm (detail)

Kevin Desbouis, Casting, 2022, wood, thread, statuettes, variable number of elements, variable dimensions

Pati Hill, Untitled (telephone), c.1977-79, serie (Common Objects), photocopy, 28 x 21,5 cm. Courtesy Air de Paris, Romainville

Kevin Desbouis, Untitled (Cake), 2022, mixed media, 50 x 35 cm

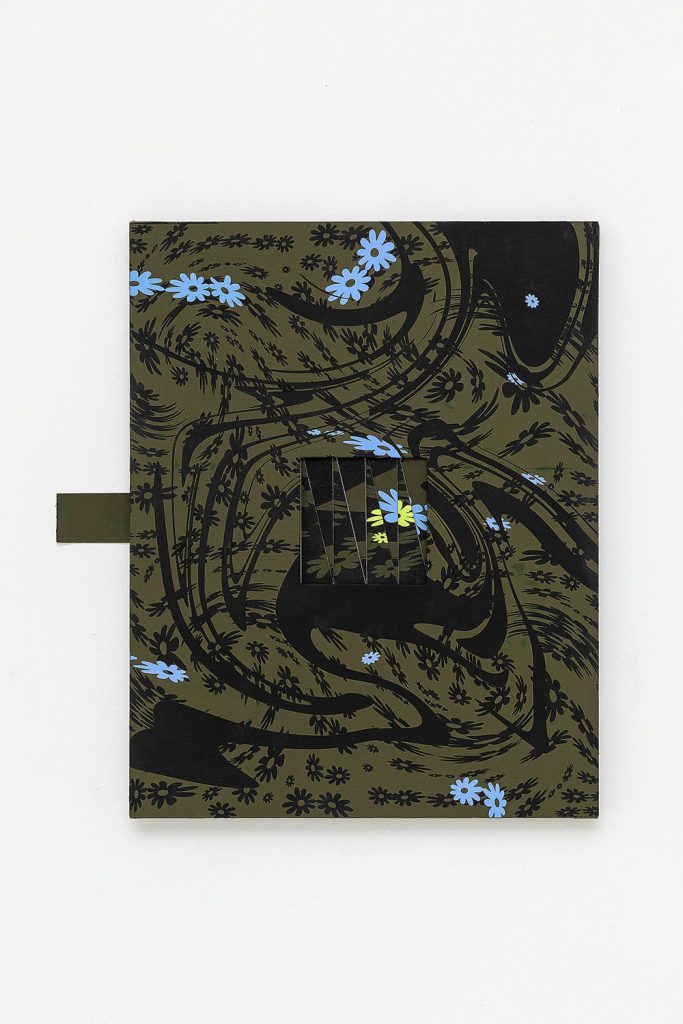

Charlotte Houette, Untitled (Green), 2022, acrylic on canvas, 60,5 x 75 cm

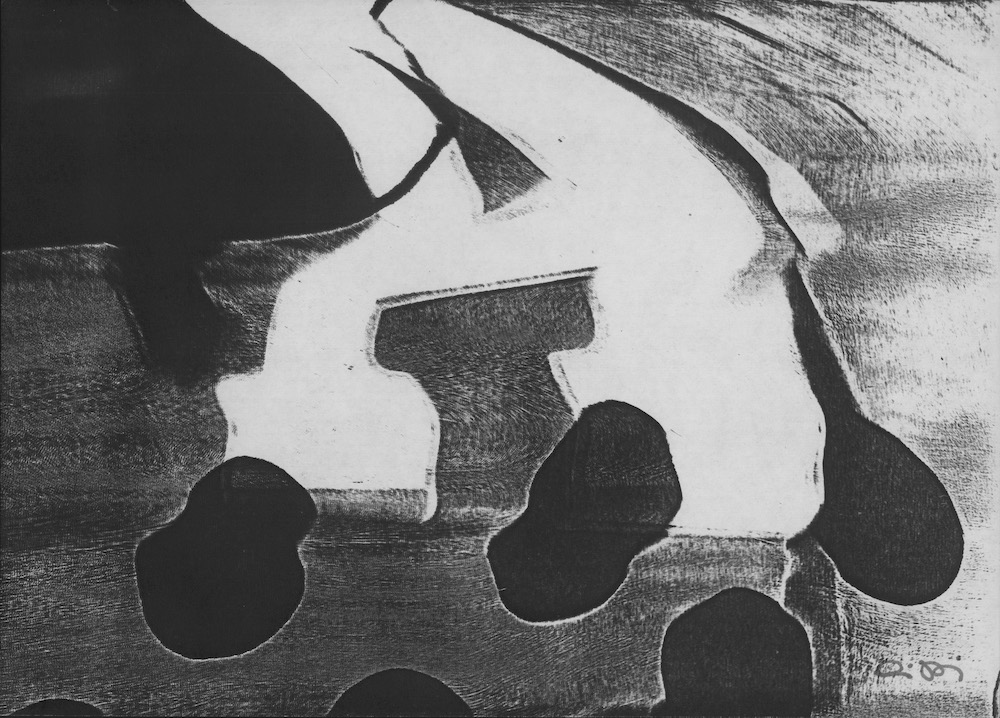

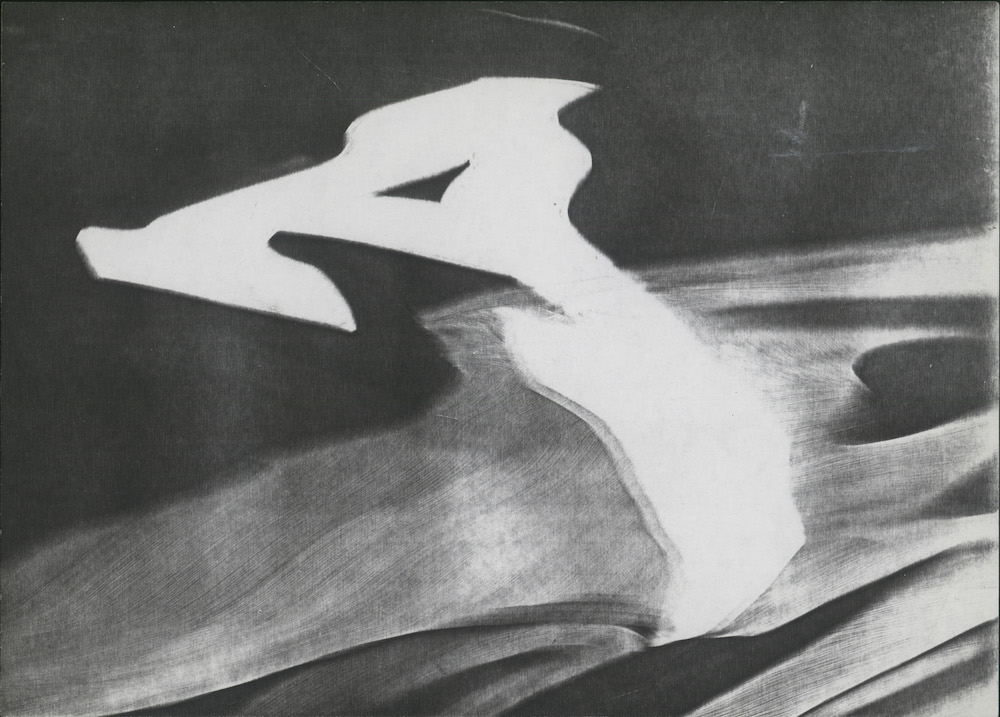

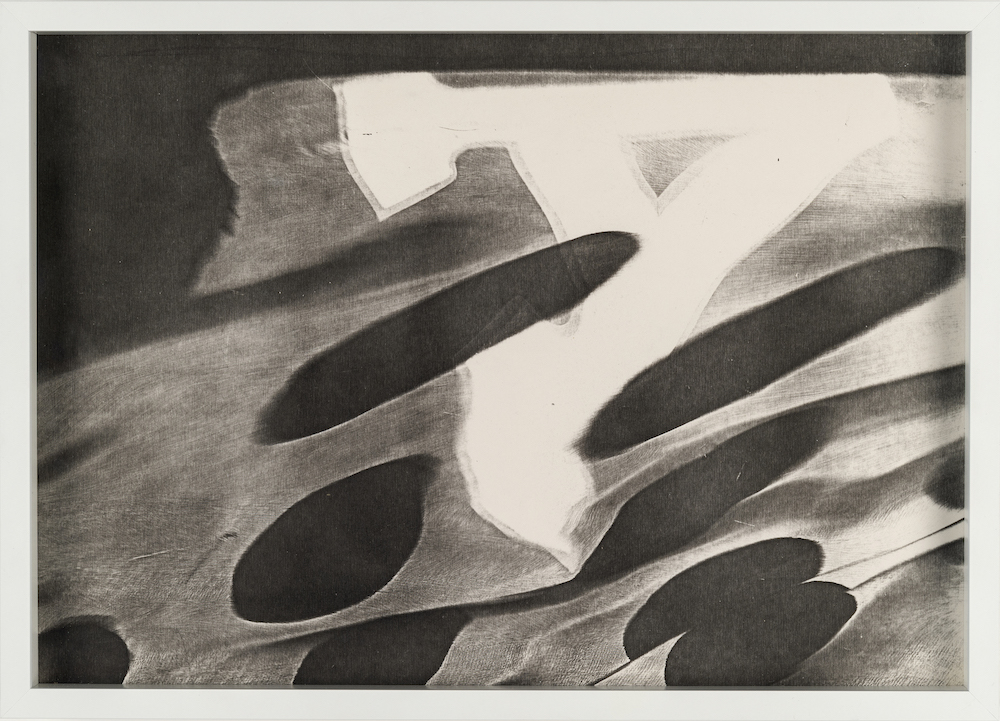

Pati Hill, Untitled, c.1980, serie (A Frolicking), photocopy, 21 x 29,7 cm (each)

Charlotte Houette, Untitled (Heart), 2022, acrylic on canvas, 60,5 x 75 cm

Charlotte Houette, Untitled (Yellow), 2022, acrylic on canvas, 60,5 x 75 cm

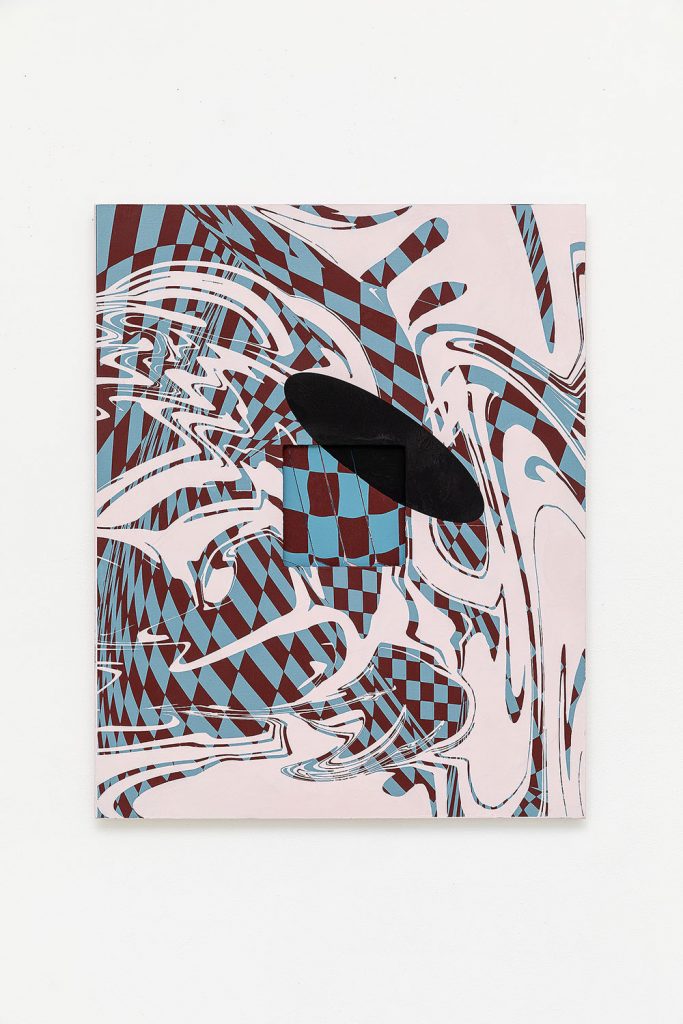

Charlotte Houette, Untitled (Pink), 2022, acrylic on canvas, 60,5 x 75 cm

Charlotte Houette, Untitled (Green), 2022, acrylic on canvas, 56 x 70 cm

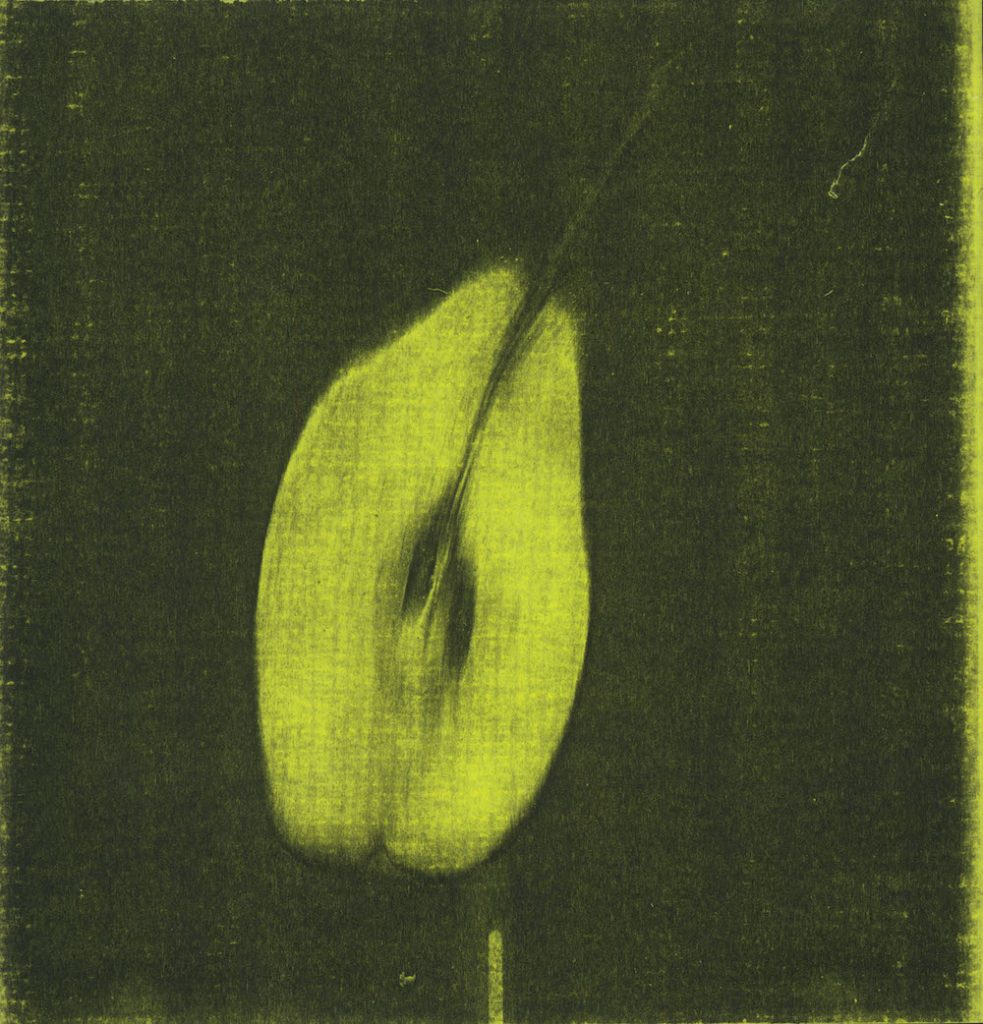

Pati Hill, Untitled (pear), c.1976, photocopy on green paper, 23 x 21,7 cm

Charlotte Houette, Untitled (Purple psyche), 2022, acrylic on canvas, 60,5 x 75 cm

Pati Hill, Untitled , c.1980, cut-out photocopy color

Kevin Desbouis, Untitled (Blue Night), 2022, voting booth, mask, mirror, cotton, variable elements, 200 x 80 x 80 cm

other people’s clothing

«Tonight, my aunt’s half-moods arrive in the room. They mirror the room and its furniture like a TV screen. They look like other people’ s clothing.»1

Insomnia and the Aunt de Tan Lin est selon ses mots un roman d’ambiance (ambient novel). Le narrateur y décrit les moments passés avec sa tante insomniaque dirigeant un motel au milieu des États-Unis. Elle dédie ses nuits éveillées à regarder le poste de télévision, et préfère les programmes rediffusés au direct. En tant qu’immigrante chinoise, l’Amérique pour elle n’est pas tant une image, ni la télévision même, mais le meuble dans lequel est serti l’écran qui lui renvoie l’illusion de son américanisation.

Depuis les couloirs anonymes du motel où les passages sont fugaces, le poste tv recouvre la réalité de la tante, il est objet, miroir, personnage. Je l’imagine zapper en continu, regarder des bouts d’émissions, late-shows, films, documentaires. En veillant, son esprit s’absenterait jusqu’à ce que la boucle de visionnage esquisse une fiction d’elle-même, avec l’intuition qu’il se produit toujours quelque chose quelque part. Délire somnolent où il serait possible de disparaître dans un décor mental à partir duquel se recomposer le monde. Le meuble tv : une boîte sans fond décorée comme un autel, une machine à incarner. Lorsque la tante disparaît, une ambigüité persiste, a-t-elle été absorbée par le poste de télévision ou n’en était-elle qu’une pure émanation ?

Il ne s’agit pas tant de chercher une réponse, mais de préférer l’aspect générique de la question, jusqu’à ce que la tante ne soit plus qu’un personnage, le meuble tv un objet domestique.

other people’s clothing réunit Kevin Desbouis, Pati Hill et Charlotte Houette. De l’extérieur, les formes choisies par leur motif, leur valeur ou leur littéralité qui investissent l’espace d’exposition ne semblent pas à leur place. Mais dans l’espace liminal du ready-made, elles y sont, et apparaissent – entre autres – comme un accessoire à activer, un cloisonnement de l’espace ou une image. Ces objets qui nous accompagnent portent en eux une dissolution de contexte, de sens initial, nous approchant d’une forme de fiction ou d’editing2 de soi, dont le terme s’inscrit comme un clin d’œil au revers des pratiques artistiques exposées liées au texte, à l’édition et à la traduction. On disparaît dans un tableau comme on se glisse sous un masque. Dissimulé dans une cabine/isoloir, on en ressort et les formes s’aplatissent sous la lumière.

Kevin Desbouis propose des installations, à partir d’un répertoire de formes principalement constitué de ready-mades, dans lesquelles l’intensité ou son absence constituent un paramètre fondamental. Il envisage le travail de l’art comme un ensemble de moments, de situations non explicites ou au potentiel partiellement achevé, pouvant recouvrir des aspects tant cinématographiques, qu’érotiques, ou refoulés. Les œuvres de Kevin Desbouis produisent ainsi un mélange d’insatisfaction et de fascination, et se rapprochent de ce que Sianne Ngai a théorisé comme jugement : le gimmick, qui peut être « une astuce, une merveille et parfois juste une chose. »3 La distance entre l’objet et le sujet y courtise une possible confusion, entre déception et séduction. En ce sens, les œuvres qu’il déploie à partir d’isoloirs, dans une analogie entre le bureau de vote, la cabine d’essayage ou le confessionnal, ouvrent des situations où l’on peut manipuler ou enfiler des accessoires, ce qui ne se déroule généralement pas sans embarras réciproque. Il semble même parfois que l’œuvre et le public n’y trouvent mutuellement pas pleinement leur place. Comme si elles suivaient un script caché, les œuvres de Kevin Desbouis impliquent des modes de production au sein desquels plusieurs intermédiaires et leurs interventions respectives, influent grandement sur l’aspect final du travail.

Au début des années 70, après une pause de treize ans dans l’édition Pati Hill commence à photocopier son environnement domestique. Objets, vêtements et aliments sont enregistrés à échelle réelle par le copieur qui leur rend une distanciation sans considération nostalgique. Les xérographies de Pati Hill évacuent la fascination au profit d’une profusion, et montrent l’attention critique qu’elle porte aux objets circonscrits qui l’entourent, à leur présence4, à sa condition de femme au foyer (housewife) et à ce qui s’y produit en dehors. La machine bureaucratique assignée au travail de secrétariat dont elle s’émancipe revêtit dans l’œuvre de Pati Hill une utilisation littérale, compulsive. Sur fond de toner noir – qu’elle injecte parfois en excédent — la duplication instantanée accentue les détails et les contours. Les formes ne collent plus à leur condition d’existence initiale, mais flottent, suspendues à l’intérieur de la page. Ce travail sur copieur ne révèle pas tant ce qui est invisible à l’œil, mais imprime le revers étrange et familier des objets. L’image leur rend leur fiction, la machine leur incertitude. Machine et objets sont les outils de l’invocation d’un langage visuel.

Les peintures de Charlotte Houette fabriquent des espaces fantasmatiques. Des éléments s’intègrent comme des maquettes à l’intérieur de ses tableaux, et projettent un espace tant architectural que mental. Ces déambulations ont des effets étincelants. Entre l’abstraction et le ready-made, ces espaces sont toujours vides et pourtant hantés. Ils rappellent les constructions proches du prototype de la villa Winchester en Californie. Une maison piège-fantôme où il est dit que la nuit la propriétaire s’en remettrait aux esprits qui lui dictent l’architecture de pièces impossibles5. Les peintures de Charlotte Houette reprennent les mécanismes d’apparition et de disparition des images en pop-up. Ses œuvres créent des boucles spatiales qui trafiquent les régimes de visibilité où les motifs se répètent et s’étirent, colorent un mouvement psychédélique. Il y a dans les œuvres de Charlotte Houette une atmosphère tourbillonnante à l’effet saturé comme si jamais tout à fait réveillé, une sensation de déréalisation guettait, nous affectant autant que les effets visuels qu’elles produisent.

other people’s clothing suit une question d’attitude envisagée à partir des formes et de leur frontalité. Si l’on peut voir dans ces formes une profondeur illusoire, celles-ci seraient à traiter comme des surfaces sur lesquelles des fictions de soi déteignent comme une redistribution des rôles. Édités elles aussi, ces formes évoquent des changements d’états – certains plus dramatiques ou comiques – et des processus de visibilité altérés. Un replacement dans la réalité qui nourrit une réflexion critique sur l’existence et la présence des objets, dans lesquels une certaine intensité semble s’être engouffrée, plus érotique ou énigmatique. Percer des trous imaginaires, directement dans leur réversibilité. Ces associations de l’esprit nous mènent vers un « délire de la digression »6 généré par ces distorsions visuelles, qui suscitent des phénomènes d’absorption, afin que se créent des présences, confuses, émerveillées ou fantomatiques.

Après tout le motel de départ accueille un personnage qui ne semble exister nulle part. On pourrait aussi se rendre compte qu’il s’agissait simplement d’un rêve fiévreux, comme si l’on avait fini par s’endormir devant le meuble TV.

Fiona Vilmer, Mars 2022

1. Tan Lin, Insomnia and the Aunt, Chicago, Kenning Editions, 2011.

2. Traitement d’un texte ou d’un film consistant à modifier, supprimer, conserver ou ajouter des éléments précédant l’objet fini.

3. Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick. Aesthetic Judgement and Capitalist Form, Harvard University Press, 2020.

Dans son livre Sianne Ngai théorise le gimmick comme étant un jugement esthétique et une forme capitaliste. Le gimmick est à la fois frustrant et attrayant, il est « lié à la perception d’un objet aux promesses peu crédibles de gain de temps, de réduction du travail et d’expansion de la valeur. »

4. Texte de Baptiste Pinteaux à l’occasion de l’exposition Heaven’s door is open to us / Like a big vacuum cleaner / O help / O clouds of dust / O choir of hairpins, 12 septembre – 17 octobre 2020, Galerie Air de Paris, Romainville.

« Si elles (les oeuvres) témoignent sûrement d’un de ces « petits luxes qui accompagnent la vie de prisonnière », celui d’aiguiser une attention particulière aux choses, à leur présence, cette attention est moins délicate que critique.»

5. De 1884 à 1922 Sarah Winchester aurait séjournée seule avec les ouvriers qui exécutent les travaux de sa maison. Des articles suggèrent que sa construction

labyrinthique veille à égarer les esprits. Mais aucune preuve que sa propriétaire la croyait hantée. La maison est peuplée de fenêtres et d’escaliers fictifs et de

portes menant à des pièces disparues.

6. Julie Becker, Bernhard Bürgi, eds. Julie Becker: Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest. Zürich: Kunsthalle Zürich, 1997. p33.

“delirium of digression”. Expression empruntée à l’artiste américaine Julie Becker pour décrire son travail artistique composé d’installation, de photographies, de vidéos, de dessins et de collages.

Remerciements à Sophie Vinet, Kevin Desbouis, Charlotte Houette, ainsi qu’à Baptiste Pinteaux, Nicole Huard, et Florence Bonnefous (Galerie Air de Paris) pour la présence de Pati Hill dans cette exposition.

______

other people’s clothing

“Tonight, my aunt’s half-moods arrive in the room. They mirror the room and its furniture like a TV screen. They look like other people’s clothing.” 1

Tan Lin’s Insomnia and the Aunt is, in his words an ambient novel. The narrator describes time spent with his insomniac aunt who runs a motel in the middle of the United States. She spends her sleepless nights watching the TV set, and prefers rerun programmes to live TV. For her, as a Chinese immigrant, America is neither an image nor the television itself but the furniture in which the screen is mounted that reflects the illusion of her Americanization.

From the anonymous corridors of the motel, where passages are fleeting/elusive, the TV set covers the aunt’s reality, it is an object, a mirror, a character. I picture her zapping continuously, watching snippets of programmes, late-shows, movies, documentaries. While staying awake, her mind would wander until the viewing loop sketches out a fiction of herself, with the intution that something is always happening somewhere (else). A somnolent delirium where it would be possible to disappear into a mental scape upon which to rewrite the world. The TV set is a backgroundless box ornamented as a altar, a machine to incarnate. When the aunt disappears, an ambiguity prevails : has she been absorbed by the TV set or was she a pure emanation of the TV set ?

The aim here is not so much to find an answer but rather to prefer the generality of the question, until the aunt is no more than a character, the TV set a domestic object.

other people’s clothing brings together Kevin Desbouis, Pati Hill and Charlotte Houette. On the outside, the forms chosen for their pattern, their value or their litralness that crowd the exhibition space look like they do not belong where they do. Yet in the liminal realm of the ready-made they do, and they appear – among other things – as a prop to be activates, a partition of the space or an image. These objects that accompany us carry with them a dissolution of context and their initial meaning, drawing us closer to a kind of fiction or editing2 of the self. The term is a wink at the reverse side of the exhibited artistic practices tied to text, publication and translation. We disappear into a painting as we slip under a mask. Concealed in a dressing/ voting booth, we extract ourselves and the shapes flatten out under the light.

Kevin Desbouis proposes installations, using a range of forms mainly constituted by ready-mades, in which intensity or its absence is a fundamental parameter. He consideres the labour of art as a set of moments, of situations that are not explicit or with a partially accomplished potential, which may contain cinematic, erotic or suppressed aspects. Kevin Desbouis’ works thus produce a combination of dissatisfaction and fascination, and approach what Sianne Ngai has theorised as a judgement: the gimmick, which can be “a trick, a wonder and sometimes just a thing.”3 The distance between the object and the subject courts a possible confusion, between disappointment and seduction. Accordingly, the works that he develops using voting booths, in an analogy between the polling booth, the fitting room or the confessional, open up situations where one can manipulate or dress up with props, which generally does not happen without mutual embarrassment. Sometimes it even seems that both the work and the audience do not fully belong together. As if they were following a hidden script, Kevin Desbouis’ works involve modes of production in which various intermediaries and their individual interventions strongly influence the final result of the work.

In the early 1970s, after a thirteen-year break from publishing, Pati Hill begins photocopying her domestic environment. Objects, clothes and food are recorded on a real scale by the copier, who renders them a distanciation without any nostalgic consideration. Pati Hill’s xerography evacuates fascination in favour of profusion, and reveals her critical attention to the circumscribed objects around her, to their presence4, to her condition as a housewife and to what happens outside this condition. The bureaucratic device assigned to secretarial work, here emancipating from this context, is used in Pati Hill’s work in a literal, compulsive way. On a black toner background – which she sometimes injects in excess – the instantaneous duplication accentuates details and edges. The forms no longer stick to their initial condition of existence, but float, suspended inside the page. This work on the copier does not so much reveal what is invisible to the eye, but imprints the strange and familiar reverse face of objects. The image returns their fiction, the machine their uncertainty. The machine and the objects are the tools for the invocation of a visual language.

Charlotte Houette’s paintings create fantasmatic spaces. Elements are incorporated into her paintings like mock-ups, projecting a space that is both architectural and mental. These wanderings have sparkling effects. Between abstraction and the ready-made, these spaces are always empty and yet haunted. They evoke the constructions close to the prototype of the Winchester Villa in California5. A trap-ghost house where it is said that at night the owner, Ms Winchester, relies on the spirits that dictate to her the architecture of impossible rooms5. Charlotte Houette’s paintings reproduce the mechanisms of appearance and disappearance of books with pop-up images. Her works create spatial loops that distort the regimes of visibility where patterns repeat and stretch, colouring a psychedelic movement. Charlotte Houette’s works have a swirling atmosphere with a saturated effect as if never quite awake, a sensation of derealization awaits, affecting us as much as the visual effects they produce.

other people’s clothing adresses a question of attitude viewed through forms and their frontality. If these forms can be seen as illusory depths, they should be seen as surfaces on which fictions of self fade, and re-cast the roles. Also edited, these forms suggest changes of state – some more dramatic or comic – and altered processes of visibility. A replacement in reality that fosters a critical reflection on the existence and presence of objects, in which a certain intensity seems to have been injected, more erotic or enigmatic. Drilling imaginary holes, directly into their reversibility. These associations of the mind lead us to a “delirium of digression “6 generated by these visual distortions, which arouse phenomena of absorption, so that presences are created, confused, amazed or ghostly.

After all, the motel in the beginning hosts a character who doesn’t seem to exist anywhere. One could also realize that it was no more than a fever dream, as if one had fallen asleep in front of the TV set.

Fiona Vilmer, March 2022

1. Tan Lin, Insomnia and the Aunt, Chicago, Kenning Editions, 2011.

2. Treatment of a text or a film consisting of modifying, deleting, keeping or adding elements preceding the finished piece.

3. Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick. Aesthetic Judgement and Capitalist Form, Harvard University Press, 2020.

In her book Sianne Ngai theorise the gimmick as an aesthetic judgment and a virtual form in capitalist. The gimmick is “irritating yet strangely attractive”, it is “linked to our perception of an object making untrustworthly claims about the saving of time, the réduction of labour and the expansion of value.”

4. Text by Baptiste Pinteaux on the occasion of the exhibition Heaven’s door is open to us / Like a big vacuum cleaner / O help / O clouds of dust / O choir of hairpins, September 12 – October 17, 2020, Galerie Air de Paris, Romainville.

“True, they (the works) may signify one of those “little luxuries that went with being a prisoner“: that of a more finely honed attentiveness to things and their presence, but this attentiveness is not so much sensitive as critical.”

5. From 1884 to 1922 Sarah Winchester is believed to have stayed alone with the workers who carried out the construction of her house. Articles suggest that its maze-like construction is designed to mislead spirits. But there is no evidence that the owner believed it to be haunted. The house is populated by fictitious windows and staircases and doors to rooms that have disappeared.

6. Julie Becker, Bernhard Burgi, eds. Julie Becker: Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest. Zurich: Kunsthalle Zurich, 1997. p33.

“delirium of digression”. I borrow this expression from the American artist Julie Becker which she uses to describe her artistic work consisting of installations, photographs, videos, drawings and collages.

Special thanks to Sophie Vinet, Kevin Desbouis, Charlotte Houette, and to Baptiste Pinteaux, Nicole Huard, and Florence Bonnefous (Galerie Air de Paris) for the presence of Pati Hill in this exhibition.

Documentation available here :